Does it really take more land to produce grass-fed (pasture-based) beef compared with grain-fed (feedlot)?

That’s an experiment I was willing to take on that you’ll read about more below. The results may surprise you.

I have a hypothesis that I want to test out on this blog post: I want to find out for a fact if forage-finished beef does in fact require more land than grain-finished beef, or whether it’s a load of hot air.

This is the common rhetorical mantra repeated by several groups, more strongly the anti-livestock animal extremists, as well as the industrial agriculture promoters:

“There’s just not enough land to produce enough grass-fed beef for everyone.”

Personally, I’m tired of hearing this rhetoric again and again without having some ammunition myself to debunk such claims. This ends now; particularly in the context of just how much land it actually takes to raise a grass-fed steer versus a grain-fed steer. A future post will look more into the actual beef consumption based on the values I arrived at below.

Have you ever done a Google search to even find out if anyone has done the work to prove this? I have, and the results were disappointing. There is only one article that gives a very ambiguous comparison. Ironically, this one phrase is repeated by other articles with nothing that is genuinely original. I’m guessing this claim came from some unpublished research paper that hasn’t even been cited in the article itself because I found no reference whatsoever. This is the vague comparison I found:

“…a grain-fed cow will require three acres of land, while a grass-fed cow requires nine acres.”

I’m sorry, but that’s just pathetic.

And what makes it worse, as a major caveat, is that the very article claims that the author of that unpublished paper is partnered with a pro-CAFO (feedlot) company. That will certainly provide a major bias on any land-use analyses associated!

It’s time I pulled back my sleeves. dug out my calculator and the Excel spreadsheets, plus the CowBytes ration software, to take a really hard look at just how much land is actually required by both forage-finishing and grain-finishing cattle. This is also a great opportunity to challenge the claim that “grain-fed” requires less land than “grass-fed.” As I write this out, this will be both an adventure for myself, and for you to read through!

Contents

Disclaimer Notice:

Please note that this post is for proof of concept’s sake only! In no way does this reflect all forage, pasture, or crop yields or conditions in the real world. There are so many variances with yields in terms of tons or pounds per acre that it’s not even funny, and that is exactly why I decided to go with average values (see tables below) instead.

Much love, kudos and respect to all those producers (you know who you are) who gave me some good, solid critiques on how to further improve this post.

Thank you!

Key Points on Feeds, Forages and Cattle

Before I begin, there are several key things to understand.

- The grass will grow back after being grazed, provided it’s done so when those plants have not yet reached full maturity (i.e., seeds out and ready to be dispersed). Grain crops do not grow back after being harvested for grain or feed; not to the same yield that was first obtained at first harvest. So unlike with pasture, cropland needs to be broken up and re-seeded again in order to get another crop.

- Both forage and crop yield and quality will be dependent on precipitation, temperature (i.e., the weather), and species used. Conditions unfavourable to any forage or crop species will make for unfavourable yields; the opposite is also true. I will not be accounting for that in the calculations below, however.

- Forage and feed quality is not static. They are always prone to change based on various factors from the stage of maturity at harvest, storage conditions, weather conditions, how they’re managed, and soil quality. For the purpose of this exercise, I’m using the expected average quality of the typical feeds I’ve chosen for both types of feeding operations, particularly for the grain-finished side.

- Forages mean both grasses and forbs (including legumes). I have a pun-intended beef with the term “grass-fed” despite it being so widely used because cows and cattle voluntarily eat far more than just grass. Pastures should not be exclusively just grass, as that flies in the face of the opportunities, benefits, and necessities for biodiversity in any plant stand that can be grazed. Hence my insistence on using the term “forage-finished” instead of “grass-finished” or even “grass-fed.”

- Weaned calves are not grain-fed; they are “backgrounded.” This is important in the feeder/market cattle operation because of the fat. Cattle that are fattened up too young have far too much extraneous fat to trim off at the butcher phase. Instead, they need to be “backgrounded” or fed a high forage diet for a certain amount of time (between 6 to 12 months) before they are deemed “ready” to be put on a fattening finisher diet. This is more so a must in feedlot operations than forage-finishing operations because of how quickly an animal can fill out when put on a mixed ration diet of ~85% grain. This allows these weaned calves to grow and fill out in terms of putting on muscle rather than fat.

- To compare forage-finished with grain-finished more accurately, I’m eliminating the time period before weaning. I don’t think it fair to include the amount of feed and land required for a cow-calf pair when the start time and weight of both forage- and grain-finished animals is basically the same. Prior to weaning, the cow is consuming the most feed, whereas the calf is consuming no forage to less than half of his mother’s from birth to weaning, respectively. It would only serve to complicate matters when the cow (or dam) is included in these calculations.

- Animal type and breeding determine the age and weight of finish. There are a lot of different breeds out there and a lot of different ways to get them to the right slaughter weight/age. For the purpose of this blog, I’m purposely using a medium-framed, British-type beef breed like Angus or Hereford. The latter breed-type could have the potential for larger land-use numbers because of their size and demands for higher-quality feeds.

- All the weights used are specific according to my calculations. I’ve already done the calculations needed to figure out the bodyweight and time expected for a steer to reach finish weight. While these seem very precise, they’re only estimates compared with the real-life context of finishing cattle on grains or forages. Keep in mind that weights and times to finish are different for every animal.

- Weaning and finishing weights are kept exactly the same for both grass-fed and grain-fed steers. This is to maintain consistency from start to finish and avoid skewing the land-use results in unfair ways. As mentioned I choose a medium-framed steer finished in four different ways in two different climates. He is expected to have a carcass hanging weight of 650 pounds. This means the end-point lightweight goal, regardless of diet, is 1150 pounds.

Now we start with the scenarios of a typical grain-finished animal versus a forage-finished steer.

The Grain-finished Steer:

I start with a medium-framed weaned steer calf weighing 700 pounds. I work through some different “step-up” diets from when he enters the backgrounding phase. The first three months are feeding through winter, and the next four months are, a) continuing feeding in a dry lot/feedlot situation, or b) going on pasture. He then gets sent to the feedlot when he reaches 1050 pounds and is fed up for one month until he reaches the target slaughter weight, for his frame size, of 1150 pounds. All that is assuming that he was weaned and brought into the backgrounding phase when he was 8 months old, was 15 months of age when he entered the feedlot and was sent to slaughter by the time he was around 16 months old.

Note: I understand that there are lots of times where beef cattle have been finished and sent slaughter at an older age, like around 18 to 24 months old. Largely this depends on the backgrounding operation, and how fast (or slow) they’re getting those steers on feed and growing. Now, I’m working with a medium-framed British-type breed, that is getting the kind of average daily gains needed for growth over fatness. I could make this far more complicated by adding in a small-framed steer and/or a large-framed steer, weaned at the same age, but finished at different end-weights purely because of their frame size!

Regardless, the backgrounding period is needed for growth. If he were a Continental-type breed (like a Simmental or Charolais), he usually (not always) doesn’t need that backgrounding period and could be sent to begin the feedlot-finishing process almost immediately after weaning. However, this largely depends on when the cow-calf producer weans and sells their calves. Continental-type beef cattle have slightly different metabolic requirements where they need higher-quality feed for bodily maintenance, growth, and (cows only) lactation than British-type breeds do. Continental-type cattle are less likely to put on a lot of intramuscular fat if put on a high-energy diet at a young age because they reach maturity at a later age.

The Forage-finished Steer:

For the grass-fed/forage-finished steer, the weaning age and weight are exactly the same as above: weaned at 700 pounds and 8 months of age (born in late May, weaned by end of December). The target slaughter weight for this steer is going to also be around 1150 pounds due to also being the same frame size (medium). The age at slaughter will be around 16 months of age, as with the grain-fed steer.

Note: Depending on the animal’s frame size, finishing weights will differ for forage-finished animals. Typically you’d want smaller-framed animals than the larger-framed ones, as they take less land and less forage to feed and finish up, and you tend to get more meat from smaller animals than fewer larger ones. Also, animals with larger frame sizes and more later-maturing breeding, such as Simmentals or even Brahman-type cattle, tend to take longer to reach a decent finishing age on forage than early-maturing animals, such as Angus, South Devon, Hereford, or Shorthorn. Where an Angus or Shorthorn may take 14 to 20 months to reach ideal finish weight on forage, a Simmental, Charolais or Limousin may take 24 to 30 months, and Brahman-type may take 30+ months to be ready for slaughter. This link from Grass-fed Solutions explains more.

What Are These Cattle Being Fed?

It’s worth noting that I’ve chosen to go with average Alberta, Canada, and USDA feed/forage quality values rather than the best or the worst quality feed or forages, all for consistency’s sake. I also used the CowBytes nutritional formulation program to help me out with my calculations.

Diet of the Grain-Finished Steer

Diet of the Grain-Finished Steer

For the Canadian grain-finished steer, I’ve started him off with a dry-lot situation with alfalfa-grass hay, barley grain, and eventually barley silage.

I also include the pasture option, where he will be fed some grain. (Note the amount of forage required is reduced because at least a quarter of his nutritional requirements [energy] is met with grain consumption.) Since we are dealing with conventional production, I thought it safe to pasture this steer using continuous-set stock grazing, or a very loose form of rotational grazing that is still a form of continuous grazing in terms of mindset.

Throughout the backgrounding phase, his hay is decreased and silage and grain increased. By the time he’s in the feedlot, he’s almost completely off the hay and fully onto grain and silage. In the last 22 days, he’s been put on a finisher diet of mostly grain and silage. He is put on a “step-up” program of feeding, where changes in feed occur every 50 to 60 days, up to that last 22-day final finishing period. This is based on the link Feedlots 101 – Alberta Cattle Feeders Association.

I figured I’d do an American feedlot-finished steer simulation as well, to satisfy the inquiring minds of my American audience (you’re welcome). I just substituted the barley grain and barley silage for corn grain and corn silage. Rations are the same as with the Canadian feedlot animals, and according to this link: Rations for Beef Cattle: University of Wisconsin Extension. You’ll be interested to note the differences in the amount fed, as well as land use results from what I have calculated.

Diet of the Forage-finished Steer

Coming up with the diet for a forage-finished steer was more challenging. There are different management practices to consider, as well as differences in climate, soil type, and forage species available for the animal to eat.

Coming up with the diet for a forage-finished steer was more challenging. There are different management practices to consider, as well as differences in climate, soil type, and forage species available for the animal to eat. So, How Much are the Grain-Finished and Forage-Finished Steers Eating?

If anyone is trying something different from what I’m doing, what I need to caution you on is to never assume that a grain-fed nor a forage-fed steer eats the same amount from weaning to the point of slaughter. We are dealing with a growing animal that experiences changes in nutrient requirements and the amount that needs to be consumed on almost a bi-monthly basis. In other words, what that steer is going to be eating just after weaning will not be the same amount a few months later. You’ll see what I mean when you read more below.

I saved myself a lot of extra math and arithmetic by doing this first section on grain-fed/finishing by using a beef ration balancing computer program called CowBytes. I selected the feeds I mentioned above and based on the step-up program used for transitioning weaned calves all the way through to the final finishing phase I was able to come up with some fairly accurate values for how much to expect a steer to eat on a daily basis based on various parameters I set the program to account for. That means you don’t have to see a bunch of complicated formulas posted here, just the values I came up with.

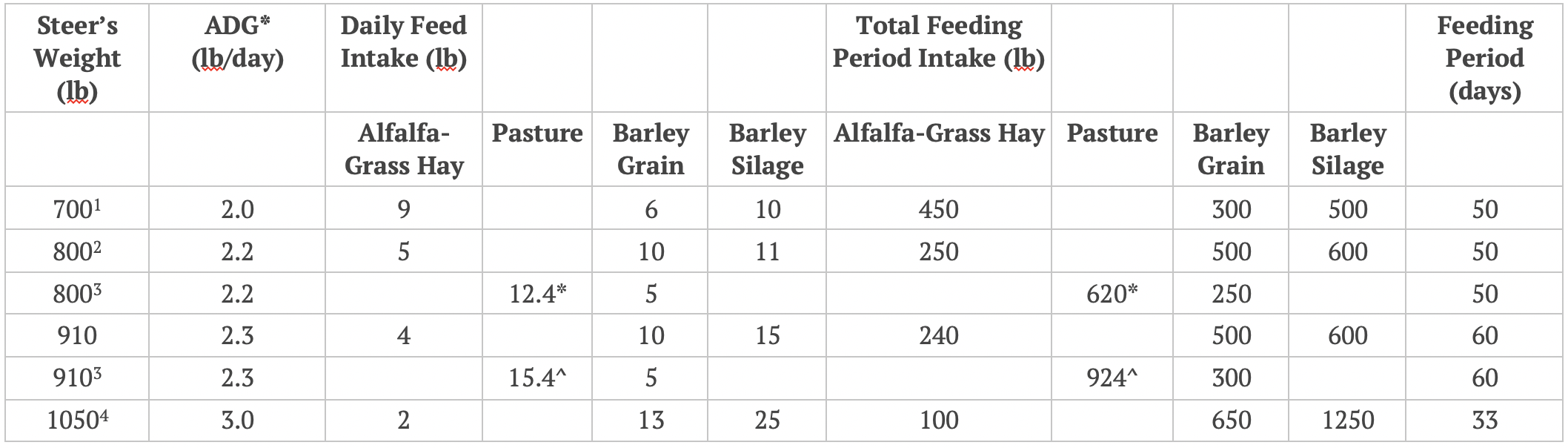

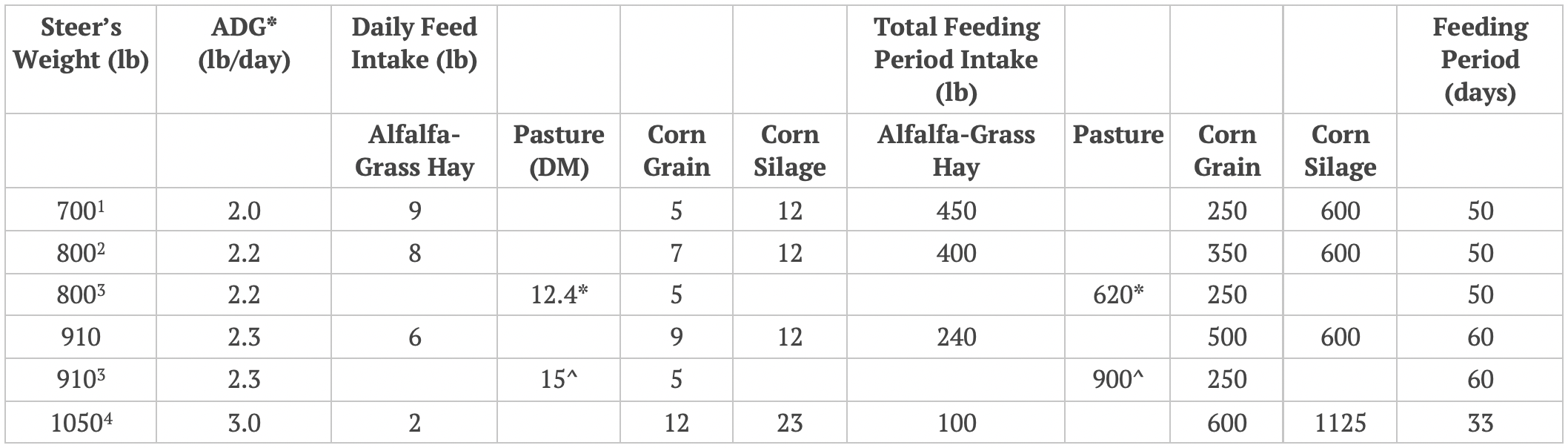

Canadian Feedlot-finished Steer Rations and Daily Feed Intake

Table 1: Feed rations from weaning to slaughter for Canadian grain-fed steer.

*ADG = Average Daily Gain, where the animal gains x pounds per unit of time (usually days); usually measured as lb/d (pounds per day) or kg/d (kilograms per day).

1 A weaned steer (8 months of age) put on to a backgrounding ration in the feedlot.

2 Assume the steer is continuing to be kept in the feedlot.

3 Pastured and supplemented with grain (for 110 days of grazing prior to entry into the feedlot). Not fed hay or silage during this time, only pasture grass of average quality.

* Expressed as dry matter (all water removed). As-fed value would be 62 pounds per day or 3100 lb over 50 days, assuming pasture forage is 80% moisture.

^ Expressed as DM. As-fed value is 77 pounds per day or 4,620 pounds over 60 days, assuming pasture forage is 80% moisture.

4 Entry into the feedlot for a 33-day finishing period up to the target finish weight of 1150 pounds.

The totals over this 12.5 month feeding period for this single steer are:

Table 2: Total consumptions for Canadian prairie grain-fed steer.

* Dry matter value. As-fed is 7,720 pounds.

π Bushel weight for barley is 48 pounds per bushel.

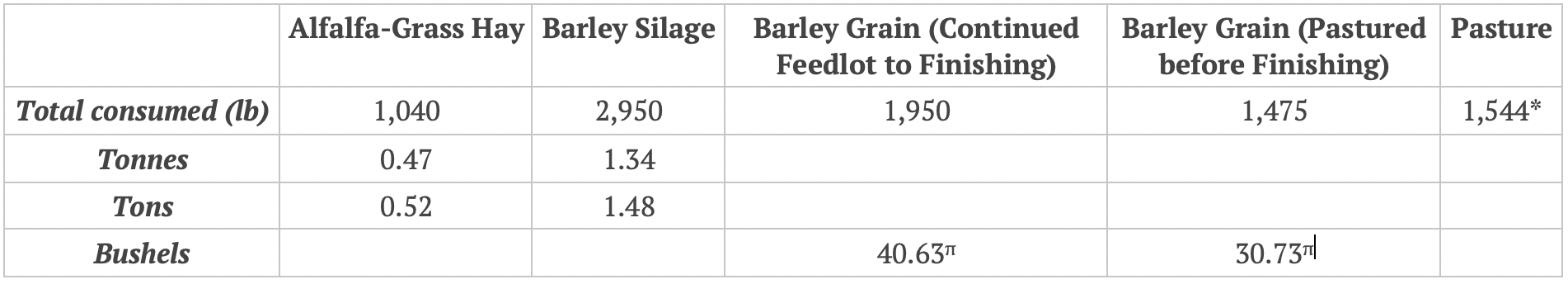

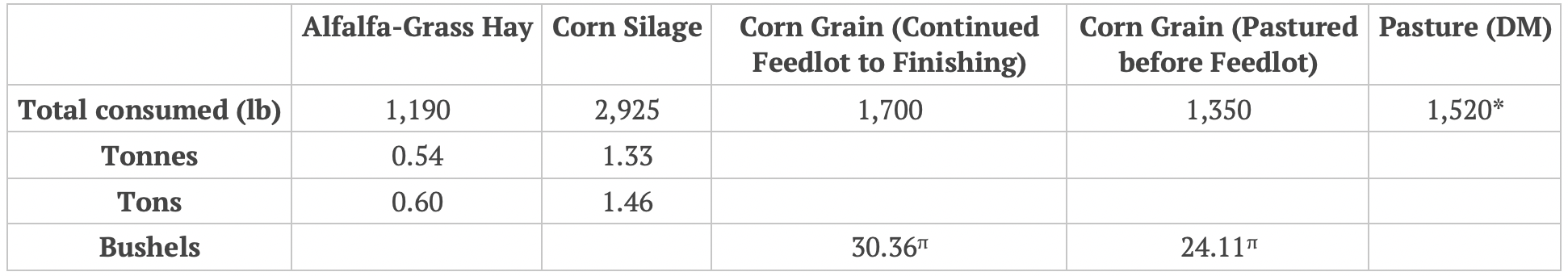

Corn (American) Finished Steer Rations and Daily Feed Intake

Table 3: Feed rations from weaning to slaughter for an American grain-fed steer.

1 A weaned steer (6 months of age) put on to a backgrounding ration in the feedlot.

2 Assume the steer is continuing to be kept in the feedlot.

3 Pastured and supplemented with grain (for 110 days of grazing prior to entry into the feedlot). Not fed hay or silage during this time, only pasture grass of average quality.

* Expressed as dry matter (DM; all water removed). As-fed value is 62 pounds per day or 3100 lb over 50 days, assuming pasture forage is 80% moisture.

^ Expressed as DM. As-fed value is 75 pounds per day or 4,500 pounds over 60 days, assuming pasture forage is 80% moisture.

4 Entry into the feedlot; the transition to an 85-percent grain-based ration (the finishing phase) begins.

5 Fed this high-grain ration until the steer reaches the target finish weight of 1450 pounds, whereby feeding stops and the steer is shipped to the slaughter facility.

The totals over this 12.5 month feeding period for this single steer are as follows:

Table 4: Total consumptions for American grain-fed steer.

* Dry matter value; as-fed is 7600 pounds.

π Bushel weight for corn is 56 pounds per bushel.

It wouldn’t be fair if I posted the land-use results now.

However, first, let’s see how much a forage-fed/finished steer would eat from weaning to slaughter from two different climatic zones.

Canadian Prairies Forage-Finishing Steer Consumption Amounts

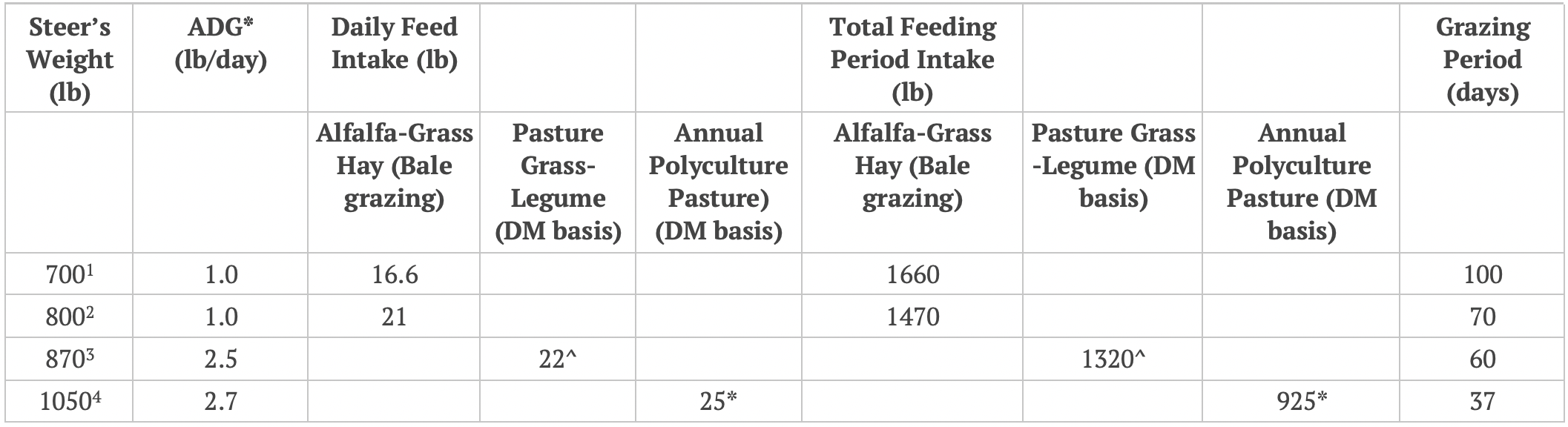

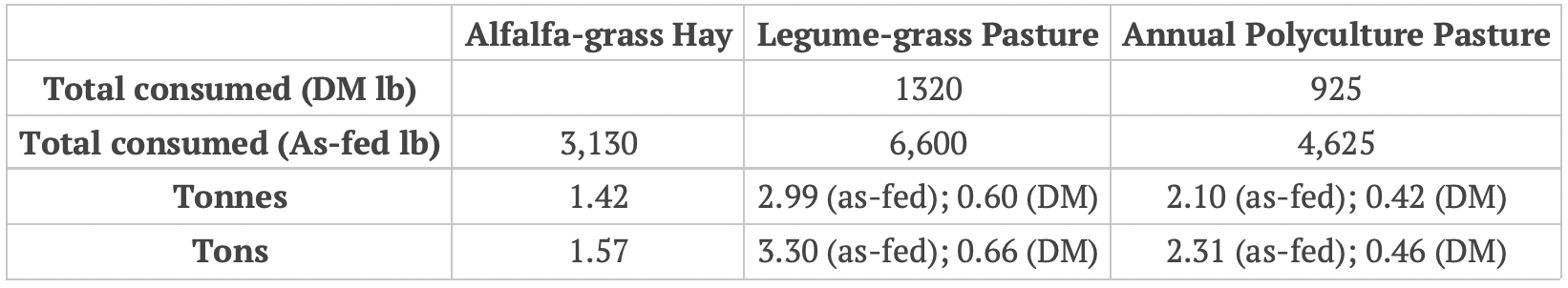

Table 5: Grazing schedule for bringing weaned steer to grass-fed finish.

1 The weaned 700-pound (~8-month-old) calf is being bale-grazed. The ADG is lower than the feedlot steer because of the advantageous slow growth in the winter due to allowing the calf to grow in terms of bone and muscle. Some may feel the ADG is too slow for a growing steer, however, we have to remember that this steer isn’t being fattened to as high a weight as what is conventionally accomplished.

2 Because this last feeding period took us up to a third of the way through March, and pastures are not yet ready until mid-May, bale grazing continues (for this scenario only).

3 Moving the steer from bale grazing to a good quality grass-legume pasture, which is ready to be grazed.

^ Dry-matter basis. Assuming pasture forage is 80% moisture, the amount consumed is 96 pounds per day or 6240 lb over 65 days.

4 Steer is moved onto a high-quality annual polyculture pasture of legumes, grasses, and some brassicas, about the same quality as the high-quality perennial legume-grass pasture he was on previously. By the time this pasture is done grazed, which would be around mid-September, the steer will have reached the target weight of 1100 pounds and be ready for slaughter.

* Dry-matter basis. Assuming pasture forage is 80% moisture, the amount consumed is 92 pounds per day or 4600 lb over 50 days.

The totals of the amount consumed overall are as follows:

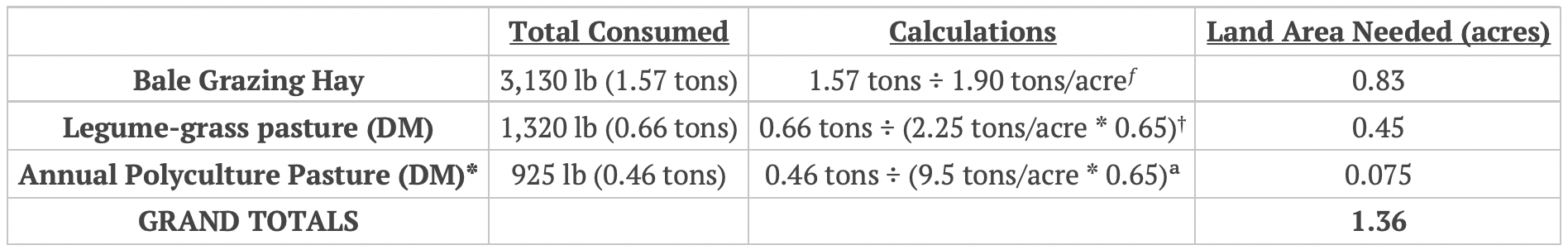

Table 6: Total consumption for Canadian grass-fed steer.

South-Eastern USA Forage-Finishing Steer Consumption Amounts

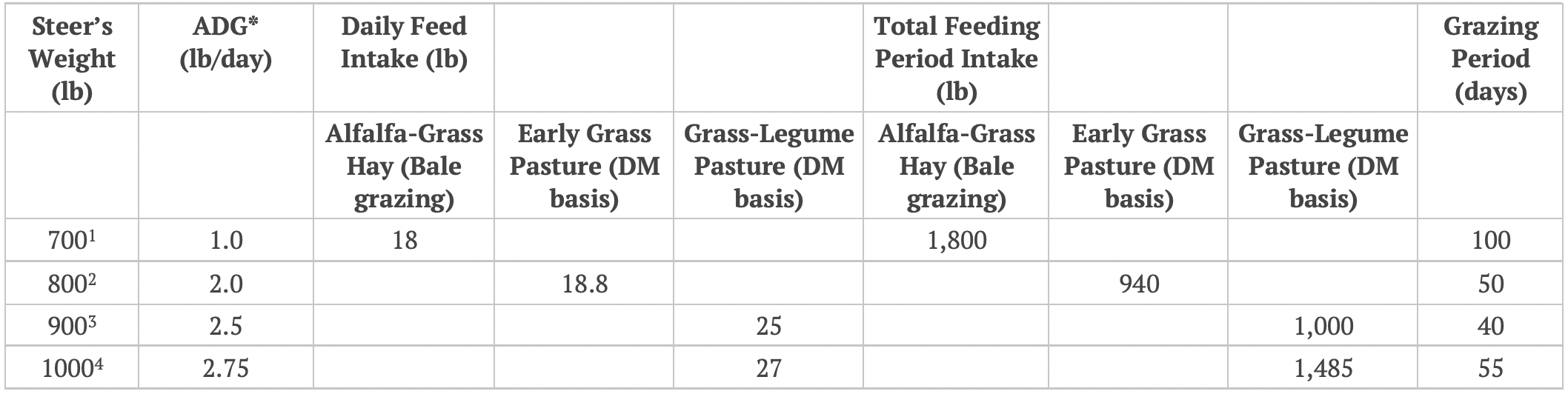

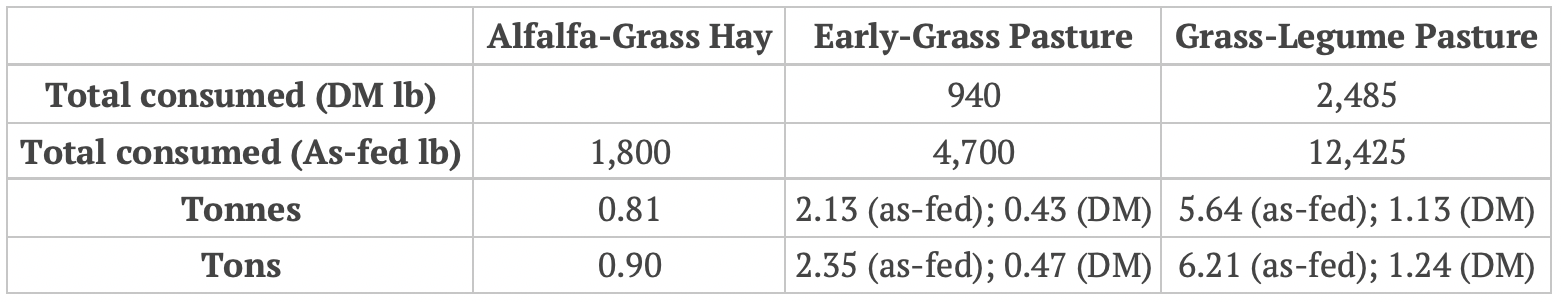

Table 7: Grazing schedule for bringing weaned steer to grass-fed finish.

1 Steer is on stockpiled pasture.

2 Steer put onto good-quality grass-legume pasture by the end of the first week of April. As-fed consumption is 90 lb/day, or 4500 lb over 50 days, assuming forage is 80-percent moisture.

3 Steer on similar high-quality grass-legume pasture. As-fed values are 95 lb/day or 4,750 lb over 50 days, assuming forage is 80-percent moisture.

4 Continue on similar pasture. As-fed values 100 lb/day or 5,000 lb over 50 days, assuming 80-percent moisture. This will get the steer up to 1100 pounds, by mid-September, by which he should be ready for slaughter.

The total amounts of forage consumed over this period (250 days) are as follows:

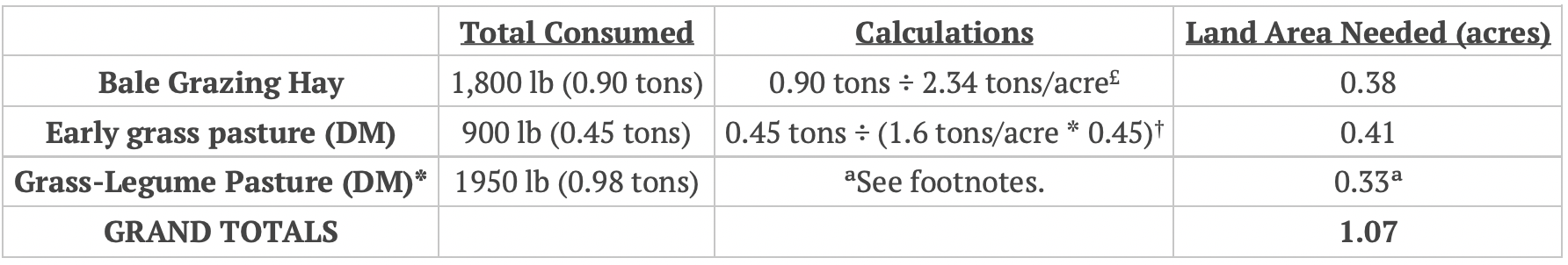

Table 8: Total consumption for American grass-fed steer.

The Land Use Comparisons of Grain-fed vs. Grass-fed Beef

There are a few things to know about how I calculated the land use values below.

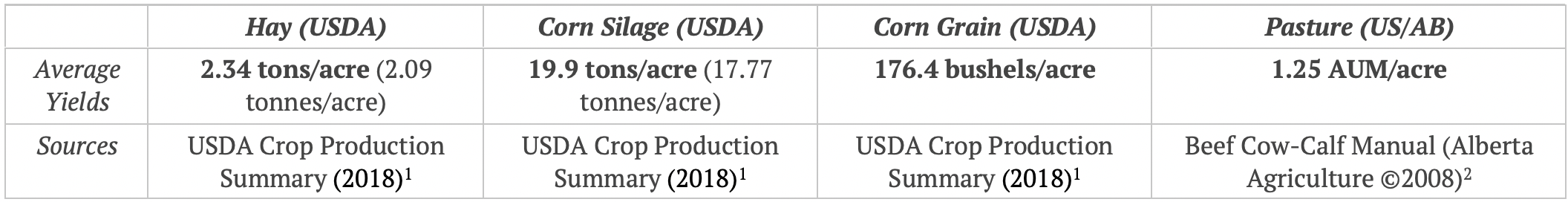

The grain-fed steer was primarily raised with stored feeds. Hay, silage, and grain yields are measured on a tonnage per acre (or hectare) basis. Since the steer is raised in Alberta, the top beef-producing province in Canada, average feed yields for that province were used and taken from national and provincial websites (sources provided in the tables below) for the calculations. The equations provided are to show how I arrived at my calculations. They can also be used for other locations.

The pasture portion of this steer was based on “good” to “excellent” quality pasture in an area that received 350 to 450 mm of precipitation. Average stocking rates (AUM/acre, where AUM = one 1000 lb cow is the standard AU consuming 800 lb of dry-matter forage per month) for this area was used to calculate the amount of land this steer needed in a continuous grazing system. (Cattle intended for the feedlot could certainly be grazed in a highly managed rotational grazing system. However, for simplicity’s sake, and to deal with fewer calculations, I choose to keep the comparisons between conventional [grain-fed] versus unorthodox [grass-fed].)

Calculating land-use values for grass-fed beef was slightly more challenging. Unlike with stored feeds, grazing involves more moving parts, making it more difficult to get averages in pasture yields. I worked with a grazing calculator made for rotational or AMP grazing. This helped me with figuring out all the variables I needed to know beforehand.

I had to estimate how much forage can be grown in a high-quality pasture in a given area, then how much is “utilized.” The utilization rate is the percentage of forage that gets eaten, trampled down and manured on. How much that steer would eat per day depending on body weight was crucial. I also had to know how long that steer would stay in a paddock, and how long that paddock would get rested. Additionally, estimating forage height and the “pounds per acre-inch” (a three-dimensional method combining volume, area, and length expected for the type of plants grown in the pasture) was needed to get approximate pasture yield.

Note that all values used to estimate yields, forage consumption, and resulting “land area needed” are all on a Dry Matter basis (all water removed). This eliminates the huge discrepancies in calculations that can be created with huge variances in the moisture content of pasture forage. For proof of concept, I allowed you to see the “as-fed” values of how much *actual* forage a grass-fed steer would eat. However, these values are ignored because of the gross difficulty in accounting for moisture content in a pasture stand.

Make sure you’re sitting down when you read this next part. I was just as shocked as you when I made the calculations.

Grain-fed Land Use Values: Canadian Barley-finished Feedlot Steer

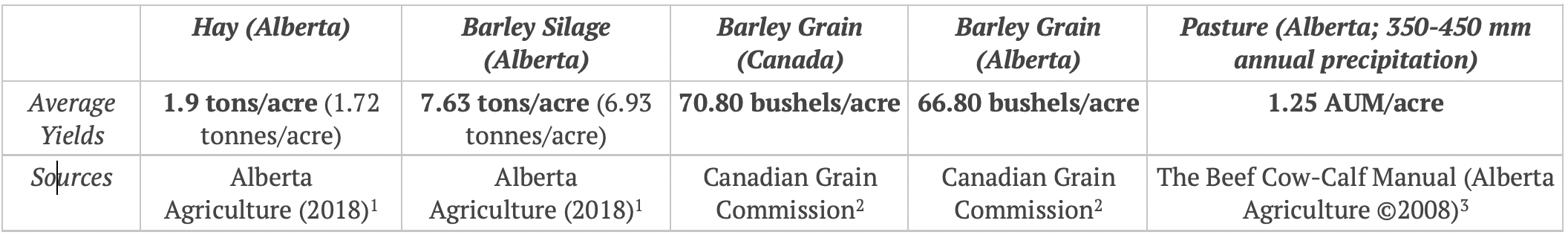

Table 9: Average regional yields of feeds used in Canadian grain-fed steer ration.

1Alberta Crop Report: Alberta 2018 Greenfeed and Silage Production Survey Results (pdf)

2Canadian Grain Commission: Quality of Western Canadian malting barley 2019 (web page).

3The Beef Cow-calf Manual 4th Ed. Free Online Version (pdf)

Taking the total amounts of hay, silage, grain, and pasture used, the amount of land used for each type of feed is as follows:

Table 10: Land use calculations for Canadian grain-fed steer.

*Good condition pasture slated to have a stocking rate of 1.25 AUM/acre (where 1 AU = 1 x 1000 lb cow with or without a calf consuming 800 lb DM forage per month [or 30.5 days]). At a 50-percent utilization rate, this meant the pasture produces 2,000 lb/acre of forage. Steer weight taken as an average ([800 + 910] ÷ 2 = 855 lb) expected to consume the equivalent amount of forage as a 535 lb steer due to the inclusion of 5 lb/day of barley grain, over 110 days (3.61 months).

†Two calculations were given to show my arrival to the same answer. The first is a standard stocking rate calculation which ignored the amount of forage consumed over 110 days, and the second acknowledged the forage consumption calculated at the predicted utilization rate (50%) for the expected forage yield of the pasture (2,000 lb/acre at 1.25 AUM/acre).

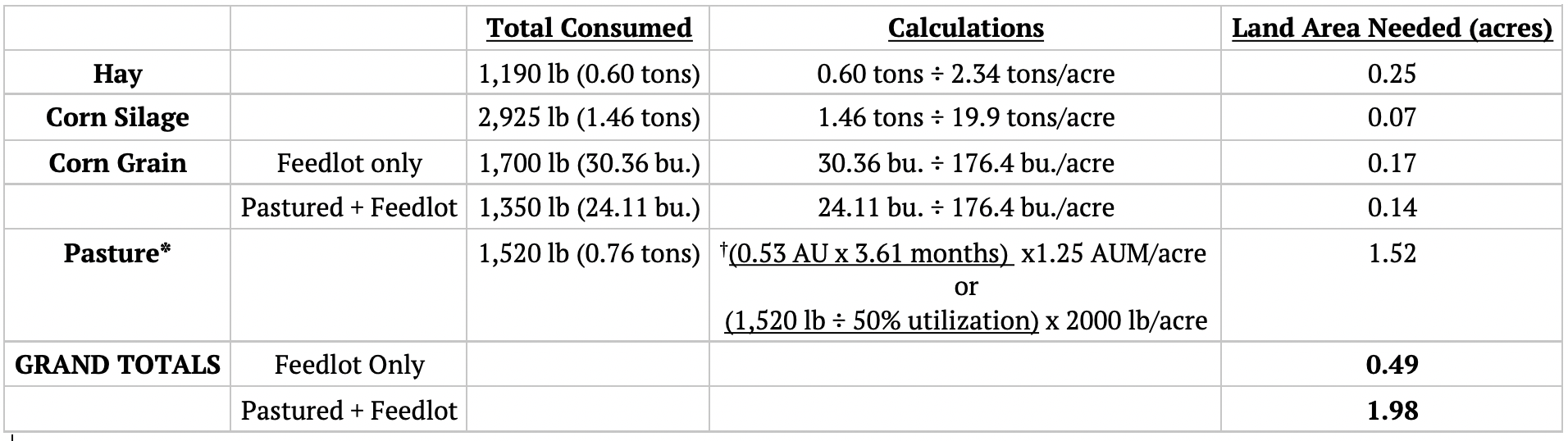

Grain-fed Land Use Values: American Corn-finished Feedlot Steer

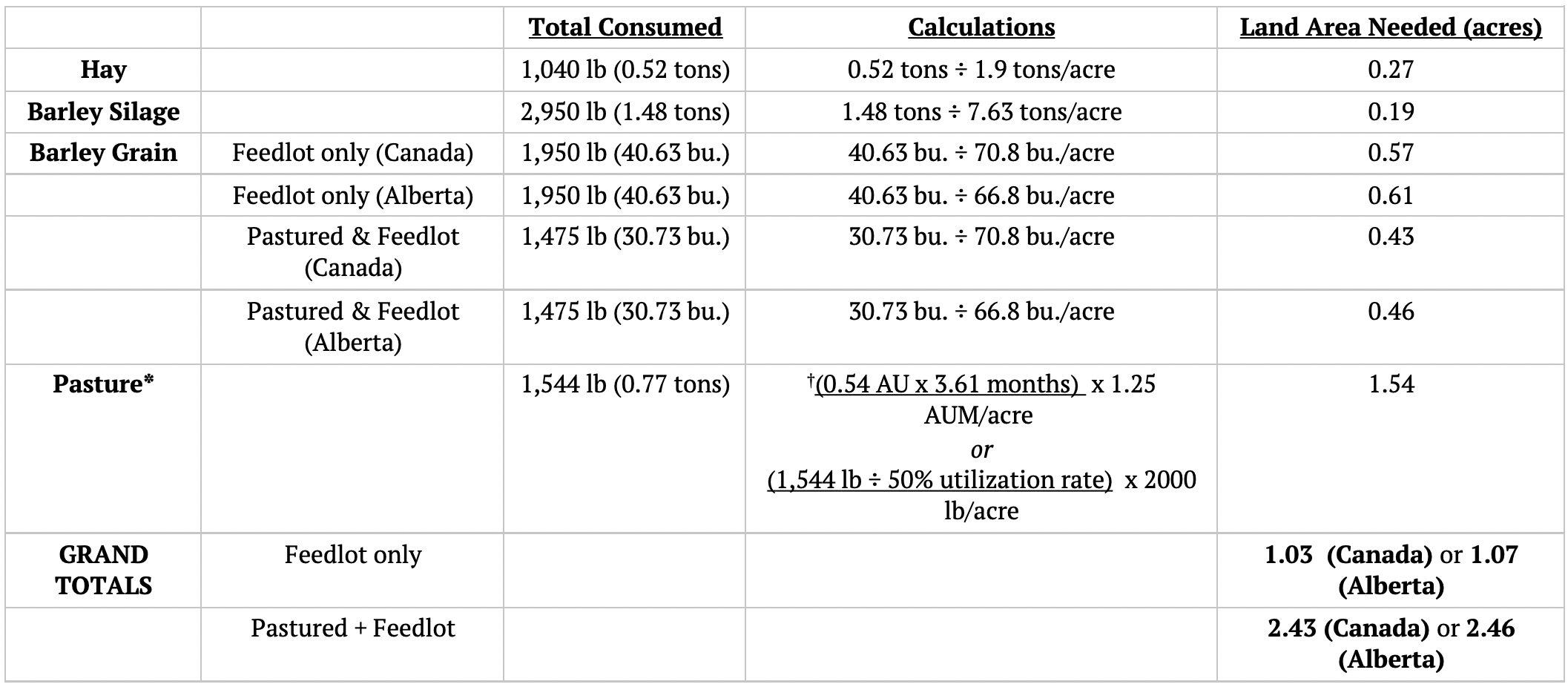

Table 11: Average regional yields of feeds used in American grain-fed steer ration.

1USDA Crop Production 2018 Summary (pdf)

2See Table 9, footnote 3.

Taking the total amounts of hay, silage, grain, and pasture used, the amount of land used for each type of feed is:

Table 12: Land use calculations for American grain-fed steer.

* Good condition pasture slated to have a stocking rate of 1.25 AUM/acre (where 1 AU = 1 x 1000 lb cow with or without a calf consuming 800 lb DM forage per month [or 30.5 days]). At a 50-percent utilization rate, this meant the pasture produces 2,000 lb/acre of forage. Steer weight taken as an average ([800 + 910] ÷ 2 = 855 lb) expected to consume the equivalent amount of forage as a 527 lb steer due to the inclusion of 5 lb/day of corn grain which meets almost half of the animal’s energy requirements, over 110 days (3.61 months).

†Two calculations were given to show my arrival to the same answer. The first is a standard stocking rate calculation which ignored the amount of forage consumed over 110 days, and the second acknowledged the forage consumption calculated at the predicted utilization rate (50%) for the expected forage yield of the pasture (2,000 lb/acre at 1.25 AUM/acre).

Forage-finished Land Use Values: Canadian Prairies Grass-fed Steer

Table 13: Land used to grow a Canadian grass-fed steer on pasture from weaning to slaughter.

ƒFor alfalfa-hay production needed for bale grazing, the hay yield from Table 9 is used. Does not include land that the bales sit on for bale grazing; only estimates the land needed to produce said hay for bale grazing.

†Perennial mixed pasture estimated to produce just above average hay yield, at 2.25 tons/acre or 4,500 lb/acre (average hay yield of 1.9 tons/acre is 3,800 lb/acre). Pasture in excellent condition, plants 10 inches tall gives 450 lb/acre-inch, which (450 * 10 =) 4,500 lb/acre. To get cow-days per acre, ((4,500 lb/acre * (65% ÷ 100)) ÷ (0.0225 * 1000) = ) 130 cow-days/acre. For one 960 lb steer (average weight was taken from when the steer enters pasture (870 pounds) and leaves at 1,050 lb) eating 2.25% of body weight with a utilization rate of 65%, grazes one 0.0074-acre (321.7 ft2) paddock grazed per day over 60 days. This does not account for how quickly grass will grow back after being grazed.

ªAnnual polyculture pasture estimated to yield 20% better than average silage value (see Table 9) at 9.5 tons/acre or 19,000 lb/acre (plants 36 inches tall * 527.8 lb/acre-inch). This gives ((19,000 lb/acre * (65% ÷ 100)) ÷ (0.0225 * 1000) =) 548.7 cow-days per acre. For one 1100 lb steer (average weight was taken from when the steer enters pasture (1050 pounds) and leaves for slaughter at 1,150 lb) eating 2.25% of body weight with a utilization rate of 65%; calculates grazing one 0.002 acres (87.30 ft2) per day over 37 days.

Forage-fed Land Use Values: South-Eastern USA Grass-fed Steer

Table 14: Land used to grow an American grass-fed steer on pasture from weaning to slaughter.

£Alfalfa-grass hay yields from Table 11 used to get yield for bale grazing. Does not include land that the bales sit on for bale grazing; only estimates the land needed to produce said hay for bale grazing.

†Early-spring grass pasture expected to yield (for the South, USA region) at only around 1.6 tons/acre or 3,200 lb/acre (400 lb/acre-inch * 8 inches tall). Gives ((3,200 lb/acre * (45% ÷ 100)) ÷ (0.0225 * 1000) = ) 64.0 cow-days per acre. Grazed at a 45% utilization rate. Spring grazing recovery is very fast, with a ~30 day recovery period. For one 850 lb steer (average weight was taken from when the steer enters pasture (800 pounds) and leaves at 900 lb) eating 2.25% of body weight, grazing in 0.0133-acre (578.5 ft2) paddock per day. The “Land Area Needed” value does not reflect the total area over a single, no-return 50-day period. Instead, it only reflects the amount of pasture used in that 30-day rotation. Over 1.6 grazing sessions, the total acres for a 50-day total grazing period (excluding rest-rotation) is 0.66 acres.

ªMixed pasture in excellent condition producing 266.7 cow-days per acre (800 lb/acre-inch * 15 inches) or 12,000 lb/acre. In terms of cow-days per acre, this is equivalent to ((12,000 lb/acre * (50% ÷ 100)) ÷ (0.0225 * 1000) = ) 266.7 cow-days per acre. Utilization rate 50%; rest period 45 days. For a 950 lb steer: grazing in a 0.0036-acre (155.2 ft2) paddock per day over 40 days gives 0.146 acres. For a 1075 lb steer: 0.0040-acre (175.5 ft2) paddock per day over 45 days (the rest period) gives 0.185 acres per grazing session (0.20 acres for 1.1 sessions over 50 days). Bolded values added together to give result.

Conclusions

One certainly can still argue that it still takes more land to raise grass-fed cattle up to slaughter than grain-fed; particularly when looking at pasture-based operations versus confinement to the feedlot. However, it’s very important to understand that all the values I used are variables. They are not fixed!

Each number can be changed to suit a particular farm or ranch operation, or region. The amount of feed–regardless of what it is–produced or pasture forage grown can and will change drastically from year to year. It depends on the management, moisture conditions, even the frame-size of the animals being fed or grazed. These change the land-use value calculations to be either less or greater than those I came up with.

The average grain and forage yields for feeding grain-fed cattle have not been shown to change much from year to year. Perhaps over a ten-year period some provincial, state, or national grain, hay or silage yields may dip (or skyrocket) one or half a ton more than “normal.” However, this is on a provincial/state or national level. A producer can see greater changes from year to year, or when comparing their yields with the neighbours’. Because of these huge discrepancies, I found it easier to go with the aforementioned averages.

It’s the grass-fed steer that I caution people to think a bit critically on. I may have invited some flack with the numbers I arrived at, which is perfectly fine. I may have created some to question my methods, which is also perfectly fine. Understand, though, that these values are approximate; they came from that which graziers have shared after they changed their management.

One other thing I should note is that the enterprises I used to raise the forage-finished steer are not limited to those I used above. For example, the American grass-fed steer could be finished on an annual polyculture pasture instead of the perennial pasture example I used. This could reduce land-use values substantially! Winter feeding practices of grass-fed cattle also aren’t limited to bale grazing; stockpile grazing or swath grazing have also been used. (What type of winter grazing to use is important when basing your decisions on your animals’ nutrient requirements. Bale grazing for growing animals seemed more logical because of the quality that good alfalfa-grass hay provides for such animals. Swath grazing and stockpile grazing, due to the poorer quality, may only be suitable for pregnant cows that are not lactating (still suckling a calf) and several months away from calving.)

I tell you though, I am just as shocked and excited as you to see these numbers. This gives me hope and reason to believe that there’s a lot more benefit to grass-fed cattle (and thus forage-finished beef) than previously thought. I guess it’s safe to say that grass-fed beef really is better for the Earth!

By the way, Dr. Allen Williams had written a guest blog piece on the Holistic Management International’s site that debunked the notion that there’s not enough land available to produce grass-fed/grass-finished beef. He showed that with even a small part of cropland converted back to pasture, and with good grazing practices that increased carrying capacity of the forage base, there would be more than enough land available for producing grass-fed beef at the same level that feedlot beef is being produced, and this is only in the United States.