When it comes to quantifying land used for either meat production or growing “plant-based foods,” things can get a little messy. I’ve been finding a lot of information gets misinterpreted. Keep this quote in mind:

“There are lies, damned lies, and statistics.”

— Mark Twain

No doubt there’s a lot of misinformation out there on the Internet. I strongly encourage you just have to use the DBEY(R/S)OTI method:

Don’t Believe Everything You (Read/See) On The Internet!

Whether I ask for it or not, I come across some really odd assortment of “information,” if you will, that makes my head cock sideways. Especially when it comes to the different vegan memes that are always inconsistent with their statistics.

Before I begin, I must admit that vegans do have it right. You most definitely can and will produce a lot more “plant-based food” (i.e., vegetables, starches, fruits, nuts, and grains) on an acre of land than you can meat (no matter if it’s rabbits, chickens, goats, sheep, cattle, ducks, turkeys… ). It’s not worth questioning that aspect of the “meat vs. veggie” argument.

However, I have several “beeves” with this simplistic-seeming fact. Those issues I addressed in the post, The Beef vs. Vegetable Land-Use Argument: Why It’s Really a Non-Issue.

The primary talking-points I really want to address here and now are the purported “truth” statistics vegans *always* use to support their side of the land-use veg vs. meat argument. Not so much the discrepancies, but what the numbers are actually telling us.

Well, maybe more me than us, but whatever.

Two memes I want to focus on have some significantly inconsistent flaws. The differences they expose in beef (or meat) amounts per amount of land required are particularly prominent. The third meme I will focus on looks at the amount of land needed for a person of a particular dietary choice to live off of for an entire year and is much more general in terms of land required for meat versus human-edible crops.

I hope you find this interesting as I did when I worked these out.

There are two major factors that are entirely overlooked in all three memes:

- Time

- How long the growing season is (Florida growing season vs. Alberta growing season)

- Daily vs. monthly vs. yearly basis

- Location

- Growing season length

- Climate

- Soil type/quality

- Annual precipitation

These get ignored because they’re variables, and variables make things quite complicated.

Contents

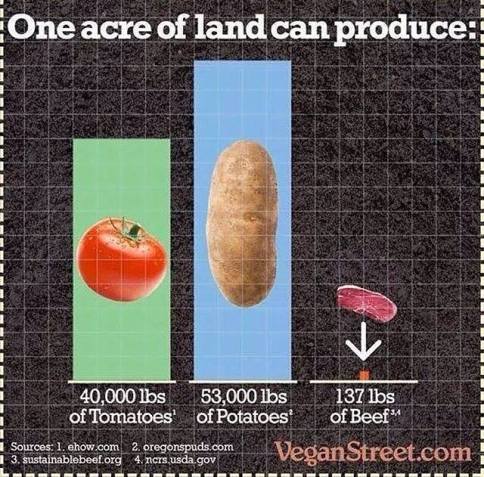

Vegan Meme #1:

Let’s look at the beef side first to see where the number above stands as far as being factually correct.

Examining the Two Sources Referencing Beef Production

Remember that time is the variable that is largely ignored. However, let’s assume that it is based on a full year of production, or one “growing season.”

I believe these two sources are used for the beef statistic:

- SBRC Environmental Benefits (from (3) sustainablebeef.org), and

- Balancing Animals with Your Forage (from (4) USDA’s NRCS).

I find the former source (3) highly unreliable for two reasons:

- The authors fail to define what an “acre-day” is in the paper. I can only assume that their “5 acre-days” versus “1.7 acre-days” means “5 acres per animal unit per day” and “1.7 acres per animal unit per day”. This leads to my second reasoning:

- To convert the SBRC’s linked articles’ statistics, 5 acres per cow-day (or AUD) (= 1 cow-day/acre ÷ 5 acres/cow-day) = 0.2 cow-days per acre; and 1.7 acres per cow-day (= 1 cow-day/acre ÷ 1.7 cow-days per acre) = 0.6 cow-days per acre.

NOTE:

1 Animal Unit Day (AUD) = 1 Cow-Day = 1 x 1,000 lb cow, with or without a calf, that eats ~26 lb (or ~2.6% of a cow’s body weight) of DM forage per day (also defined as 1 AU [animal unit]) where Dry Matter (DM) = all water removed.

From these calculations, the SBRC authors were using unrealistic and extremely low forage productivity variables for pasture land. Perhaps they were focusing on very specific regional calculations, which makes their numbers more truthful. However, to use their calculations for all locations across either the United States or Canada (or anywhere else in the world) is absolutely foolish.

In that case, the SRBC article is undoubtedly an unreliable and highly inaccurate source to reference for any meme, article, blog, or other deliverable made public.

Fortunately, the NRCS fact sheet is much, much more realistic.

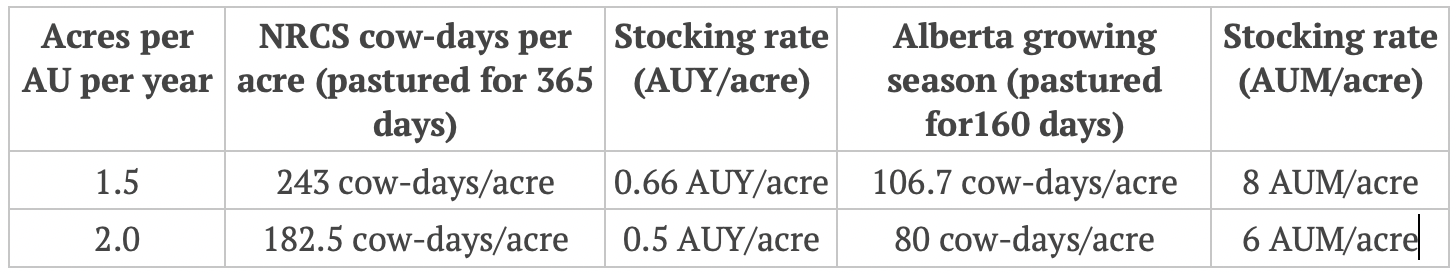

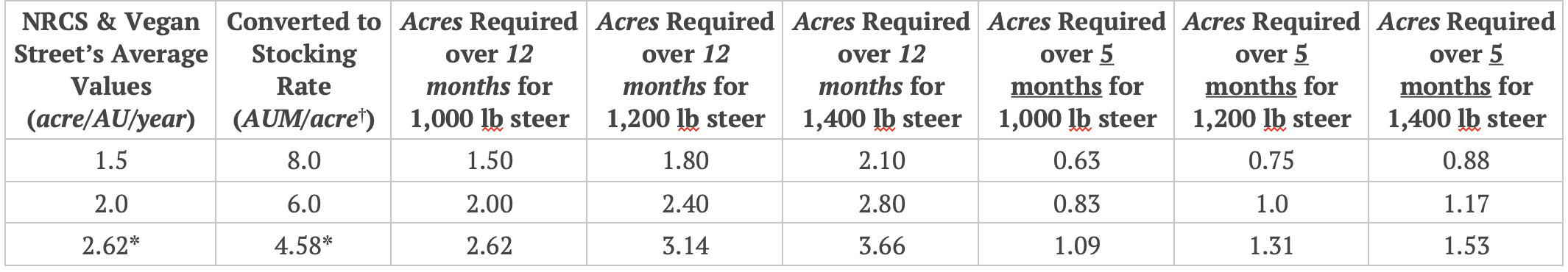

Their ballpark average for the number of acres per year per animal unit is 1.5 to 2 acres. To convert that in terms of stocking rate (cow-days per acre and AUM/acre):

Much better.

Working Out Vegan Street’s [Boxed] Beef Number (Is It Accurate?)

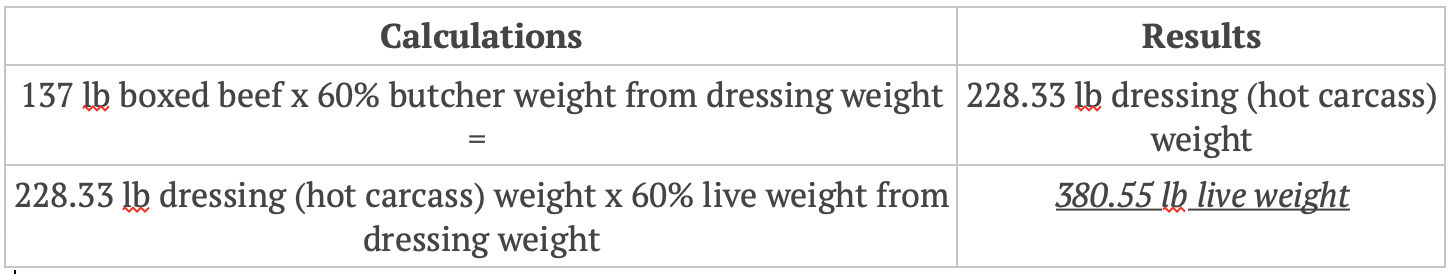

Vegan Street has established that 137 lb of beef is the number that compares to the tonnage of potatoes and tomatoes produced. There is no mention of whether this is beef from a carcass or actually boxed-and-ready-to-serve beef. I have to make another assumption here and believe that it’s the latter. Let’s assume an average dressing weight is 60% of the live-weight of your regular beef steer (or hot carcass weight after all organs, head, legs, tail, and hide is removed), and 60% of that dressing weight is boxed beef (various cuts of steaks, roasts, and ground beef). Based on that, I work the value backwards:

At first glance, we can’t help but point out how extremely small (or light) in weight this beef animal really is! However, we must remember that this is based on merely one acre that a single beef animal is on for, supposedly, an “entire year.” Or, an entire growing season.

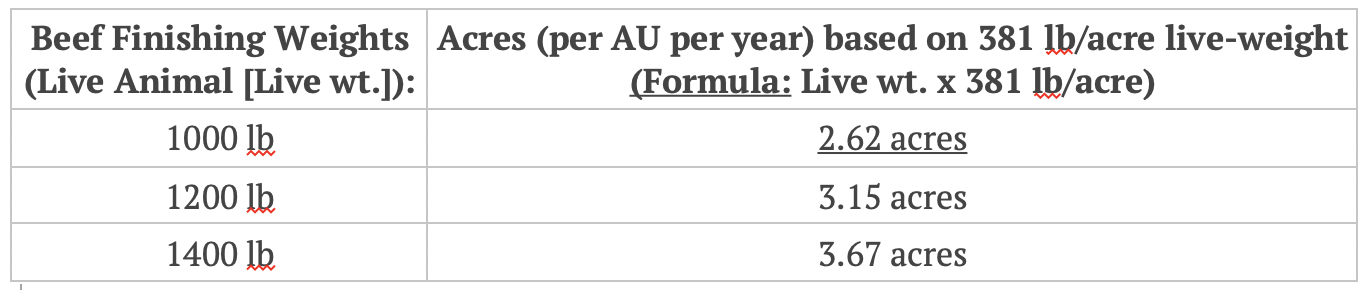

Since we know that the finishing live-weight for cattle, depending on the frame score (see Target Slaughter Weights: Are Your Beef Cattle Fat Enough for Market) ranges from 1000 to 1400 lbs, and using the standard animal unit, we can figure how many acres the meme is actually referring to. To make calculations easier, we will round up the live weight value we got to 381 lb.

To calculate how many acres Vegan Street assumes 381 lbs of live weight takes up, based on three different finishing weights of beef steers:

As you’ll see, the acreage values do not address the question of time. How long does it take to finish a steer to that weight? How long is the grazing season for the steer before slaughter (it’s not always 365 days of the year)? There’s also the question of what feed is being fed. Are these values assuming the steer is 100% grass-fed or 100% feed-lot raised, or a 60-40% or 40-60% mix of both? What’s the tonnage of pasture or hay or silage or grains produced for the steer?

I’ve actually answered much of these questions using average values in the post, Another Land-Use Debate: Feedlot-finished vs. Forage-finished.

One thing in common I can see from the table above is that the assumed stocking rate I calculated out is 4.58 AUM/acre or 139.3 cow-days per acre. This will be significant when we compare it with the NRCS values.

The Acreage Required Comparison with NRCS vs. Vegan Street

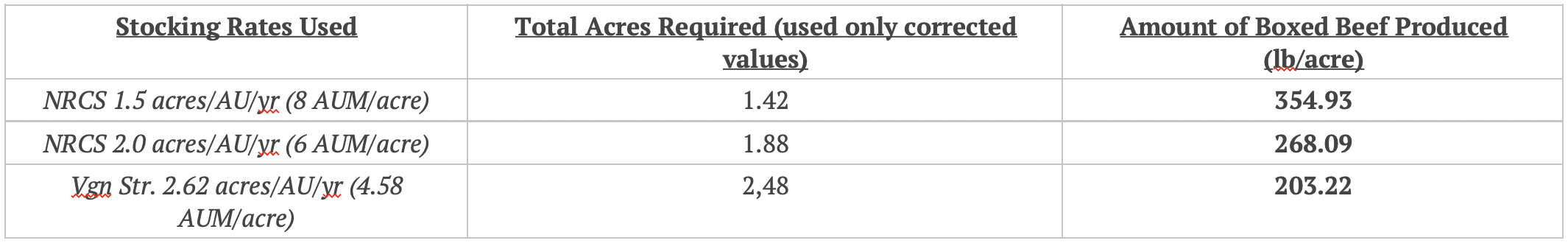

With that lovely segue, let’s use the NRCS values (where I converted to stocking rates) to see:

- The acres required for a 1,000 or 1,200 or 1,400 lb finisher steer grazed for 12 months and 5 months based on the two NRCS values; and

- The acres required for a 1,000 or 1,200 or 1,400 lb finisher steer grazed for 12 months and 5 months based on the stocking rate calculated from Vegan Street’s 137 lb boxed beef per acre.

This is where a table especially comes in handy.

*2.62 acres/AU/year and 4.58 AUM/acre come from the Vegan Street 137 lb boxed beef/acre calculated above.

†An AUM/acre is one animal unit (1 AU = 1 x 1000 lb cow with or without a calf) consuming one month’s worth of forage (~800 lb/month) per acre.

The calculations sure speak for themselves! From what I calculated out, it looks like Vegan Street should never have used the NRCS values either because the stocking rates for both “average” values (1.5 acres/AU/year and 2.0 acres/AU/year) are significantly higher than the stocking rate value that Vegan Street used to get their 137 lb/acre of boxed beef! In fact, more beef per acre will be produced according to NRCS than what Vegan Street has proposed in their meme!!

The validity of this meme certainly is now in serious question. However, we must note that this meme used forage production values from the southern United States where there is assumed grazing all year round, and forage production is quite high. Other areas of North America will often see pastures (and rangelands) with much lower amounts of forage produced per acre. For example, here in Alberta, the best productive dry-land (non-irrigated) pasture is assumed to have an average stocking rate of 2.0 AUM/acre. Other pastures, particularly in the drier south, may only have < 0.5 AUM/acre especially if the health of the pasture is poor. Certainly, significantly less beef per acre will be produced from such low-yielding stands.

Regardless, certainly, NRCS’s values call out a bit of the accuracy of Vegan Street’s attempt to scare us all away from eating beef, cuz “taking up too much land!!” Yes, land which is unsuitable for growing tomatoes and potatoes in the first place…

Another thing I find interesting is that I believe the calculations reveal Vegan Street’s attempt to discredit grass-fed beef. I may be just making yet another baseless assumption, but it causes me to think… particularly since I worked on that other article (see above) comparing feedlot to forage-finishing in two different regions of North America with several different forage/feedlot rations.

Speaking of which, let’s look at the reality behind feeding–and finishing–a “grass-fed” steer for meat.

The Reality of Grass-Finishing a Grass-Fed Steer

Realistically, a single steer raised for slaughter is not going to be eating the same amount of forage from the first year of purchase to the end of his life.

A steer is started on the feeder program (feeding for when he gets turned into beef) when he’s weaned. The normal weaning weight for a feeder steer is 600 pounds, where he is ~6 months old. From there we begin to calculate how much he will be eating.

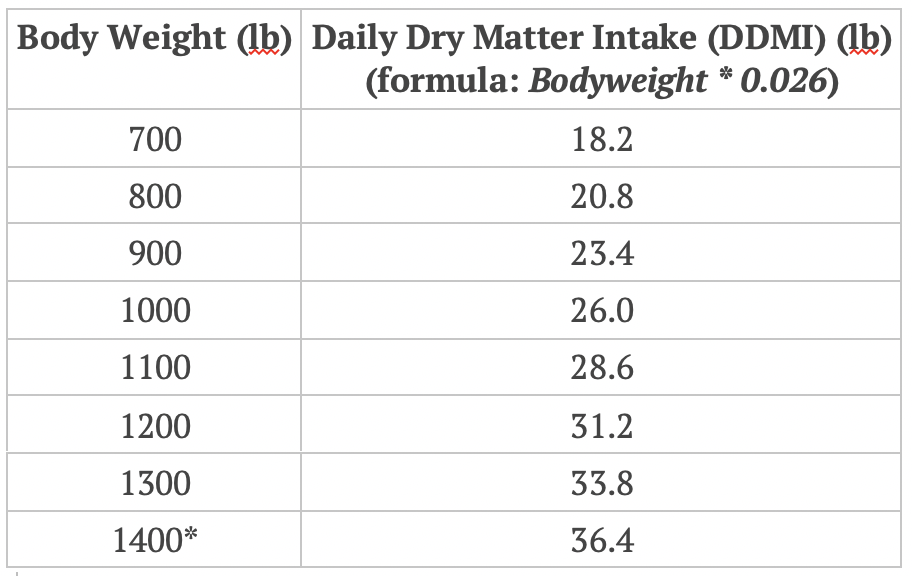

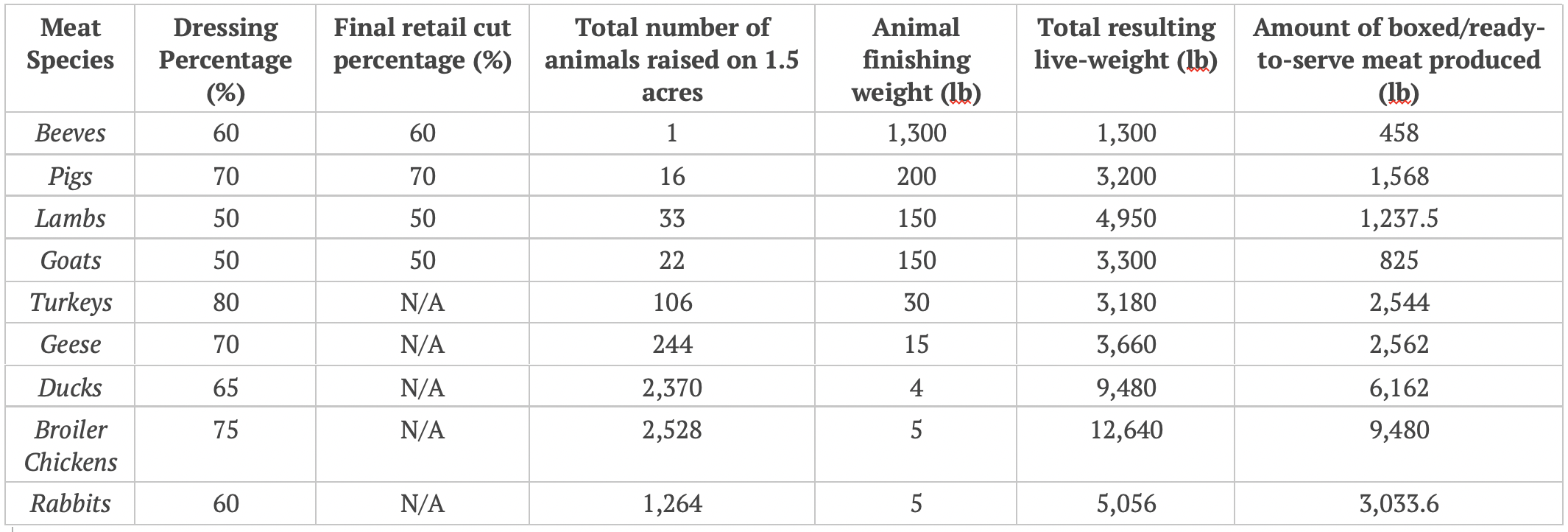

At 600 pounds he’s eating about 15.6 lb of DM forage per day (= 600 lb bodyweight * (2.6% bodyweight consumed feed DM per day * 100)). The larger in bodyweight he gets as he grows and fills out, the more feed he will need to eat. If that steer’s target slaughter weight is 1400 pounds, then the daily dry matter intake (DDMI) would increase for every 100 pound gain in body weight:

*Counting at this weight only for dry matter intake comparison context.

For a steer to get to 1400 lb in one year, he would need to have an average daily gain (ADG) of 2.2 pounds per day.

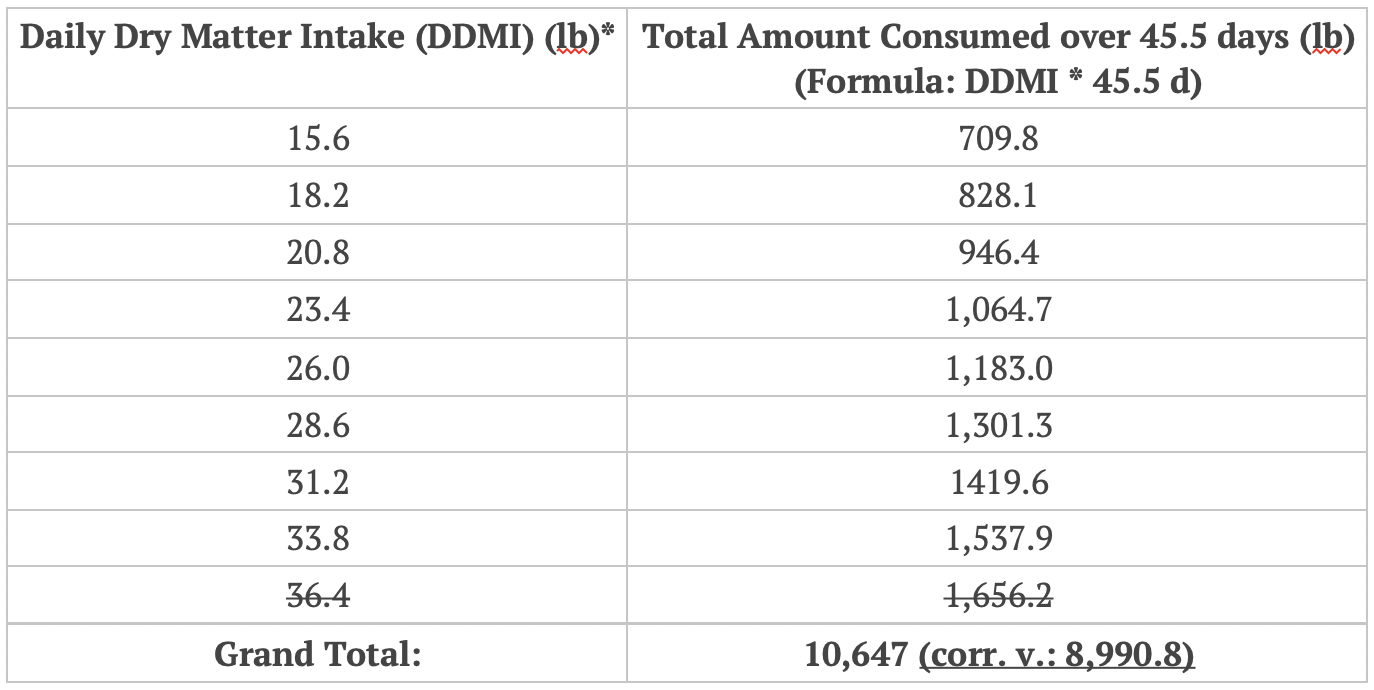

If we were to estimate how long it takes that steer to gain 100 pounds at that rate of gain it would take him to get from 600 pounds to 700 pounds (for example) in 45.5 days. From there we can estimate how much feed that steer is going to need over 45.5-day intervals. In other words, we can calculate how much feed a steer is going to eat over 45.5 days, but taking into account the 100-pound incremental difference that a steer must go through before reaching that target finish weight.

I won’t bore you with the math. But to demonstrate, yet again, just how much feed a 600 lb steer, to get to 700 pounds, needs to eat (on a dry-matter basis) over 45.5 days, I use this calculation:

15.6 lb DDMI * 45.5 days = 709.8 lb DM feed

I use the same calculation for each hundred-weight increase over a 45.5-day period. Then I add all those values up to get the total amount of feed that steer will need.

You’re probably wondering why I’m going to all this trouble to determine how much a steer will eat in one year (or 364 days). Stay with me, we’re getting there.

When raising cattle on grass, the important thing to remember is: Grass will grow back. It will grow back readily particularly if you are using Management-intensive Grazing (or Holistic Planned Grazing®). This may allow for at least two grazing sessions per season; it also permits you to plan when to move the animals to the right place for the right reasons.

Now, 10,647 lb (actually 8,990.8 lb total consumed) because once that steer reaches 1400 pounds, it’s not going to be spending any more length of time grazing; he’ll be heading to freezer camp very soon) of required forage to grow that steer can be easily met in a highly productive area, such as the range that NRCS has set out.

Let’s put that in perspective. NRCS’s estimate of 1.5 acres per AU per year gives us 12,800 pounds of forage per acre, not including a utilization rate of 50 percent. That’s more than enough forage yield to meet the needs of a growing steer going from 600 to 1400 pounds over 13 months. (This is especially true considering that the stocking rate calculations can only account for one weight “class” at a time.)

Not only that, but Vegan Street’s own 137 lb of boxed beef per acre shows that forage yield notwithstanding (it’s more or less implied), gave me 2.62 acres/AU/yr. By my calculations, that translates to 4.58 AUM/acre, which is derived–with a 50% utilization rate–from assuming that the land produces 7,335 lb/acre of forage. That forage yield gave me 141.06 cow-days/acre (scroll up to see what 1 cow-day equals.)

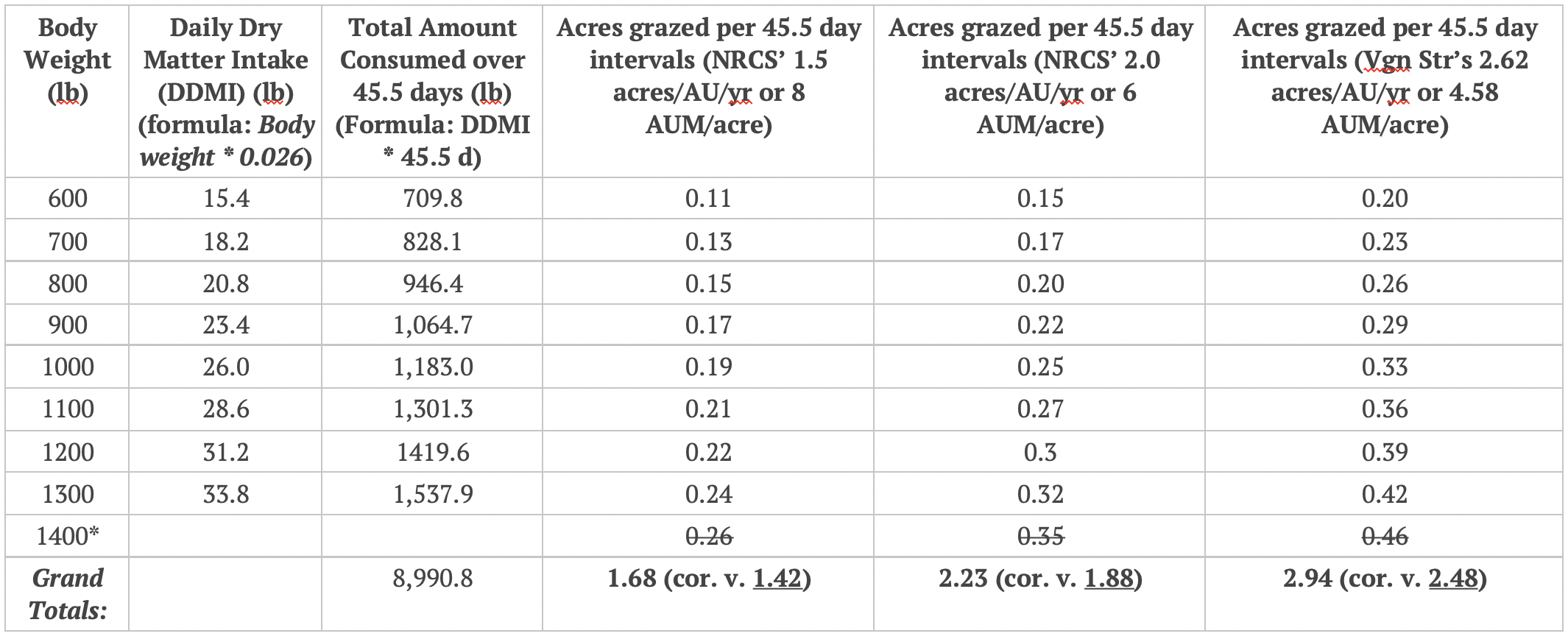

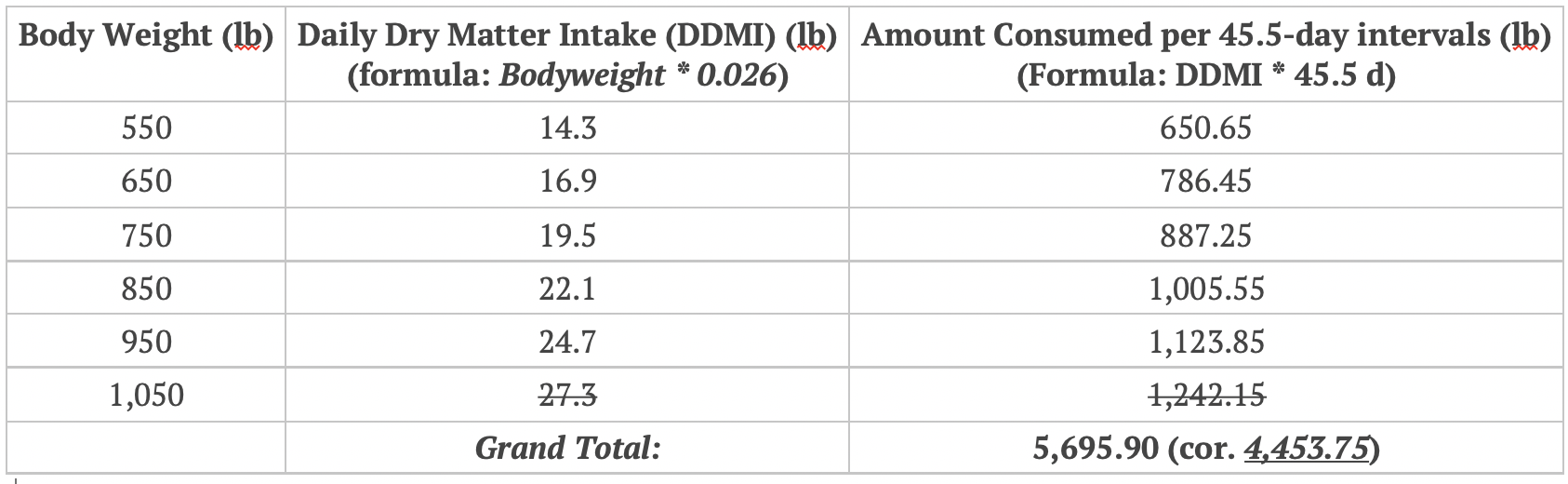

Since I’m on a roll here, I’ve created a table that uses the three stocking rate values from NRCS (2) and Vegan Street (1) to show just how much land is *actually* needed to grow a steer to finish. Using that 45.5-days weight gain session (ignoring all other variables such as compensatory gain, and changes in forage yield according to seasonality) that takes a 600 lb steer to 1400 lb over 409.5 days, and based on the DDMI values calculated above, we get an accumulated total of land used over 409.5 days.

You wouldn’t believe what I did next. I took those values and calculated out how much boxed-beef could be produced on a per-acre basis; basically, I set out to prove if the Vegan Street meme is in fact correct, or not.

Vegan Street has some explaining to do!

Why did I get a value that is 48% greater than theirs? Did they miscalculate? Did I miscalculate? Did they use a smaller animal than the industry average? I would love to know!

Not only that, but NRCS’ two values gave us boxed beef per acre weights that are 96% and 159%, respectively, greater than Vegan Street’s meme “average”! Very curious…

If you remember how the average amount of boxed beef can be expected off a live animal, the value you should get is 504 lb of boxed, ready-to-serve beef off a 1400 lb finisher steer. (Calculation: 1400 lb live wt. x 0.6 = 840 lb carcass wt x 0.6 = 504 lb boxed beef butcher wt.)

The ultimate question that all of this leads to me (and us) is:

Is the Vegan Street meme correct on its boxed beef number?

My answer isn’t yes. It should be, but it’s not. Instead, it’s It Depends. I’m sorry, yet not sorry, to say this.

I already mentioned to you how there are many variables at play here. There are variables which I gave some hints at above; such as huge variances in both location and time of year (seasonality) on forage productivity. As you will have seen in the NRCS linked article above, forage production is never the same throughout the entire year. Some months are abysmal, others are over-the-top excellent. Moisture conditions can also play a role in how well (or not) forage productivity in a pasture will do. More rain (to an extent) will give more forage for livestock to eat versus less.

Not only that, but these values don’t take into account the fact that grass grows back after being grazed. One or more of these acreage values may need to be grazed again 30, 45, 60, 90, or even 120 days later! In other words, these pastures, we should call them, could be grazed not once, but twice, thrice, maybe even four times over one year. It all depends on the moisture and growing conditions, and a location’s climate.

This means that the proposed amount of beef produced on one acre could be underestimated, just based on that very concept.

A fantastic point that NRCS pointed out was the Surplus vs. Deficit forage amounts in the South (USA) compared with what a certain number of animals actually *needed.* Deficits are, as mentioned, a result of seasonality or short of moisture. Because animals need to eat, such deficits must be filled in with supplement feed sources; like hay. Otherwise, if kept on pasture without making up for that deficit, those animals will undoubtedly starve to death. Nobody wants that!

Could you *potentially* produce 504 pounds of boxed beef on just one acre? Honestly, I wouldn’t doubt it. This would have to be on an extremely high-productive area that receives adequate moisture all year round and bolsters a significant amount of forage all year round. Like, say, on pastures that are very close to the Equator. Would that be the maximum amount of beef that can be produced on Earth? Unless someone proves me otherwise, I can’t see why it wouldn’t be. But don’t ask me what the maximum amount of beef can be produced per acre, because I’ll just give you the same answer as I gave earlier: IT DEPENDS!!

Potatoes & Tomatoes: What can Actually be Produced per Acre?

The easy answer is that it is highly variable. It really depends on soil type and quality, moisture, cultivars used, location, organic vs. conventional, climate/weather conditions, etc.

Vegan Street claims that 53,000 lb of potatoes and 40,000 lb of tomatoes can be grown per acre per year.

I did a little digging, as usual.

Let’s start with potatoes first.

How Many Potatoes Per Acre?

The source that Vegan Street used was OregonSpuds.com. I took a look at it; according to their Potato Trivia page, I found the following statement:

Oregon has one of the highest yields per acre of potatoes in the world at 53,000 pounds of potatoes per acre!

Other sources that I dug up had a few different statistics to share. Average yields differ quite substantially from year to year, and for different areas. Some examples I pulled from a Google search:

- Current USDA source found that Oregon had a bumper crop of 60,000 lb/acre in 2018. Washington also had a nice bumper crop in the same year of 63,000 lb/acre. The highest-known potato-producing state, Idaho, only had 45,000 lb/acre in 2018. (See next bullet for source.)

- See page 8 for yield per acre stats for the potato-producing states in THIS DOCUMENT from USDA-NRCS. The average yield for the USA in 2019 is 45,300 lb/acre.

- The average Canadian potato yield is 34.39 tonnes/hectare (or 30,290 lb/acre) according to the Canadian Horticulture Canada Potato Production in Canada document.

- Organic Irish-variety potatoes would yield 15,200 lb/acre (Gardens of Eden Crop Yield Verification)

No doubt a lot more potatoes can be produced per acre than beef. But we have to remember that, nutritionally, potatoes are deficient when it comes to protein content and other vitamins and minerals compared with beef. Potatoes are a starch “vegetable,” meaning that most of the edible tuber is comprised of carbs. In 100 grams of potato, there is 20 g of carbohydrates and only 2 g of protein. Beef has a lot more protein, at 22 to 26 g per 100 g.

How Many Tomatoes Per Acre?

I found even more extreme variabilities with tomato production.

Vegan Street, for some weird reason, linked to eHow.com as their only legitimate source for tomato production. For one thing, eHow.com is kinda one of those “wiki”-type websites that need to be taken with a giant grain of salt. For another, it’s not as reliable a source for statistics as something like USDA or Statista. However, because I was curious, I tried to find the article Vegan Street got their 40,000 lb/acre from. No luck. What a shame.

The best source I could find that came close to the value they used was not from eHow.com, but rather from GardenGuides.com. Again, shameful. According to that much-more-trustworthy link (bolding is mine):

On average, one acre of tomatoes will produce slightly more than 1,500 [x] 25-pound cartons, or 37,500 pounds of red, ripe fruit. About 5,000 tomato plants are required to meet this number.

Tomato growers will plant between 2,400 to 5,800 tomato plants per acre. How much each plant will yield in one growing season is variable, but most suggest to expect between 10 to 30 pounds of tomatoes per plant. Some folks are capable–if they’re using the right varieties and ensuring good growing conditions–of getting 50 to 80 pounds of tomatoes per plant!!

This means, on a per-acre basis, 2,400 plants on an acre may yield between 24,000 lb/acre to 192,000 lb/acre. If a person had 5,800 plants per acre, then they could expect to get between 58,000 lb/acre to 464,000 lb/acre of tomatoes!

Those are some significant variabilities. See Tomato Production, Hunker’s Link on Tomato Production per Acre, and eXtension.org’s Field Production of Organic Tomatoes for more information.

Conclusions for Vegan Meme #1

Obviously, without a shadow of a doubt, more plant-based foods are going to be produced per acre per year than meat will. That’s a no brainer.

What Vegan Street hasn’t told us is the huge variabilities that can make a difference between a bumper crop and a massive crop failure.

The other thing that Vegan Street hasn’t ever told us is the distinct advantage that livestock has compared to crops is simply legs vs. roots. I talk so much more about this in Beef vs. Vegetable Land-Use Argument Part 2.

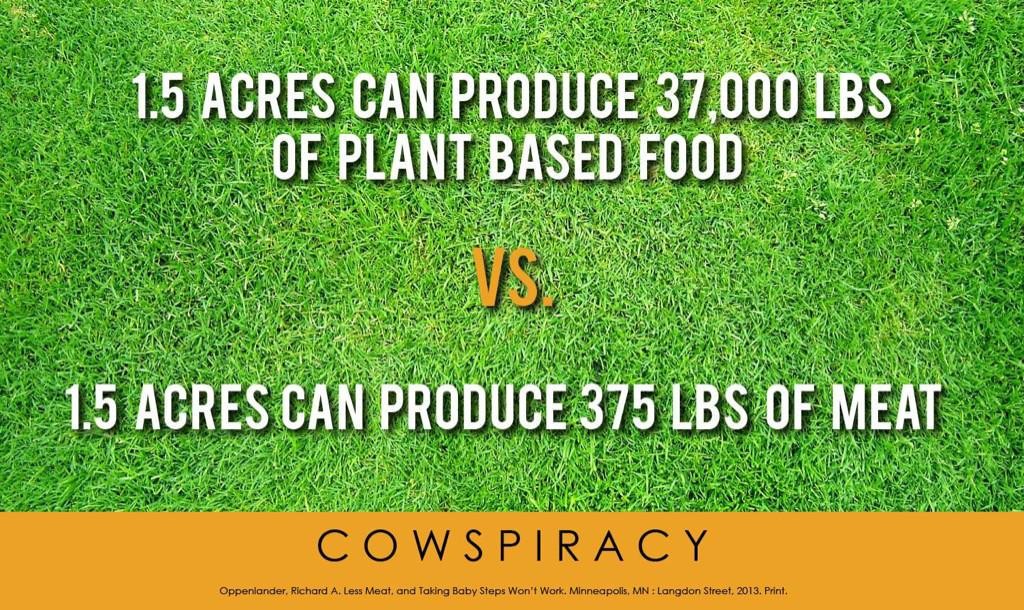

Vegan Meme #2:

This meme–over 5 years old now (since editing this post in December 2020)–comes directly from the Cowspiracy Facts page. It’s still floating around as “truth” amongst many a vegan fan of this joke of a documentary. Ironically enough (and I may have had something to do with it), the authors of that Facts page corrected their verbiage to “beef” instead of “meat.”

Before I get into the analytical part of things, I must say that the creators of this meme did a terrible job in providing a useful source. The source in tiny print at the bottom is actually from a book that Dr. Richard Oppenlander wrote in 2013 called “Food Choice and Sustainability: Why Buying Local, Eating Less Meat, and Taking Baby Steps Won’t Work.” It’s basically a shit opinion piece of 223 pages that proselytizes why everyone should go vegan. What’s worse is that, other than that book, there is no other legitimate scientific, unbiased source where these stats come from. (And there’s no damn way I’m going to waste US$26 on a worthless book I just need one little source from. Sorry, not sorry, Ope.)

Want something even more disappointing? Cowspiracy Facts page can’t even provide sufficient worthy sources to assert this very claim they’ve made public. The Johnny’s Selected Seeds link? Broken. Here’s the correct link that Cowspiracy website admins are too lazy to fix. The Iowa State University 2012 link on Grass-fed and Organic Beef link on–get this–production costs and market prices is laughably irrelevant. The only part that *may* be relevant is one little line on Table 5 (page 7 out of 11 in pdf file) that states “Total pounds of beef produced per acre grazed.” And yet, the value they arrived at is altogether different–even if calculated to 1.5 acres per the meme. Shameful.

You know, if Oppenlander et. al. makers of Cowspiracy really want to promote the truth about industrial agriculture and the *evil* animal agricultural industry, they could do a lot better job with their sources. Good, reputable, and accurate sources really, really help with maintaining competency, credibility and integrity for being a reliable source of information to better inform people about where their food comes from. That means staying on top of fixing broken links, and not sourcing from one’s own deliverables lest ye be accused of conflict of interest.

If they’re reading this, and sweating bricks over it, good. But I’ve got more where that came from. Stay tuned, because I’ll be releasing a massive Cowspiracy critique like nothing you’ve ever read.

For now, I will focus on breaking down the numbers of this meme alone and ignoring the new (albeit too-little-too-late) correction mentioned above.

Just like with the Vegan Street meme, I will work with the *meat* side first.

There three major things wrong with using the term “meat” in this meme:

- It’s far too vague a term. “Meat” is a very broad term that does not just equate to beef, as we worked with above.

- Meat, by definition, is “…the flesh of an animal, typically a mammal or bird, as food (the flesh of domestic fowls is sometimes distinguished as poultry)” (from Oxford Dictionary)

- One and a half acres can produce much more meat than indicated above. However, this differs from one species to another due to space requirements (dictated by body size), the amount of feed consumed, and how quickly an animal is ready for slaughter. (For example, chickens need less space and eat less and reach slaughter weight sooner than pigs, and pigs more so less than cows, in that order.)

Already, just knowing those latter two details puts the validity of this meme into serious question!

This meme makes things far more complicated than you think. It also discredits itself because it ignores what is making it overly simplistic. See, if it’s going to be stating that 375 pounds of MEAT (not beef, not pork, not… you get the picture) produced on 1.5 acres, then someone (a.k.a me)needs to do a bit of work to break those numbers down to brass tax. Let’s look at some things:

- How many animals (and their size) does it really take to make up 375 pounds of meat?

- Given the time it takes them to reach slaughter weight;

- How many animals of each species can be raised for a year on 1.5 acres?

- How many animals can 1.5 acres hold to be raised for meat per year?

- How much meat of each different listed species can actually be produced on 1.5 acres?

Here’s the thing. Completely ignoring where I pointed out the recent correction above, there’s doubt that they’re talking about BEEF being produced from that 1.5 acres, NOT “meat.” I’ll bust that apart after I get through the numbers here.

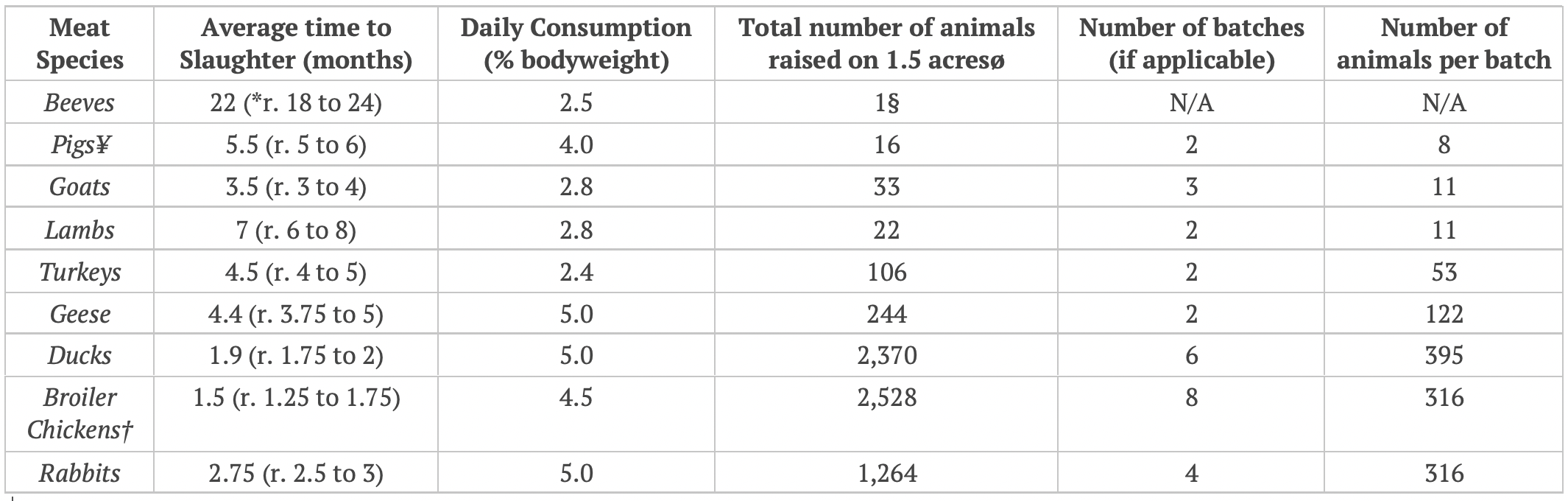

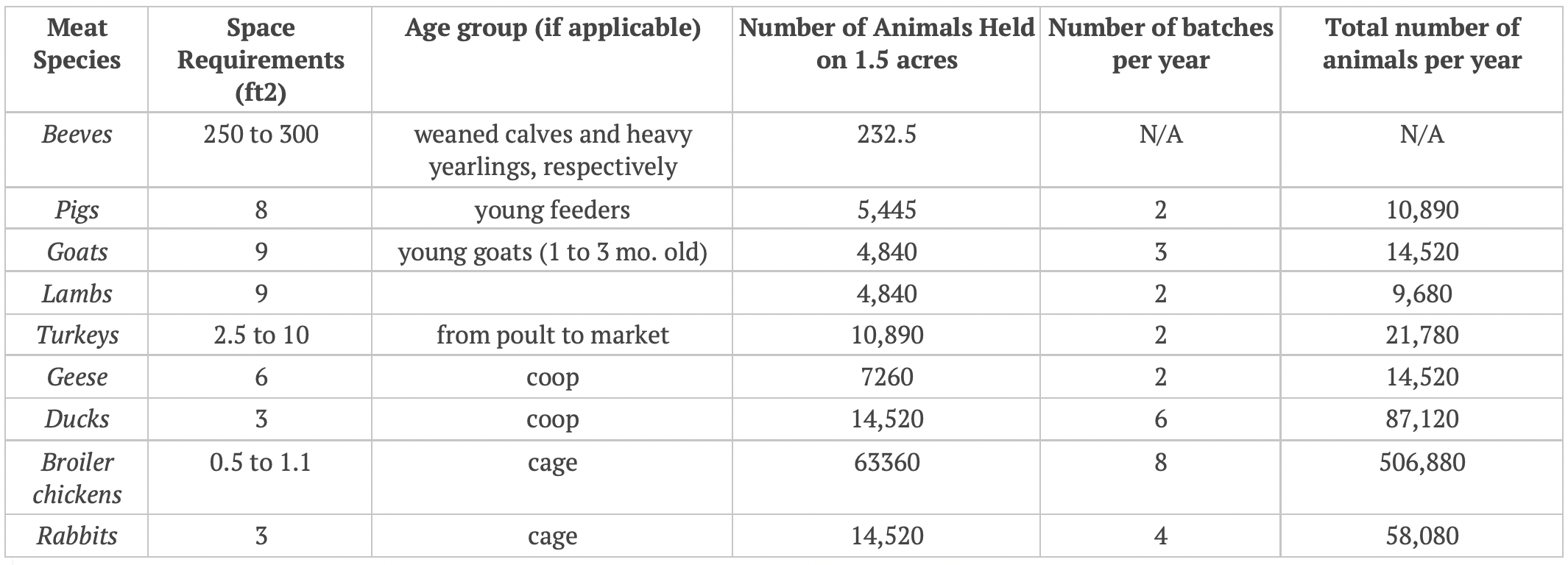

How Many Animals of Each Species can 1.5 Pastured Acres Raise?

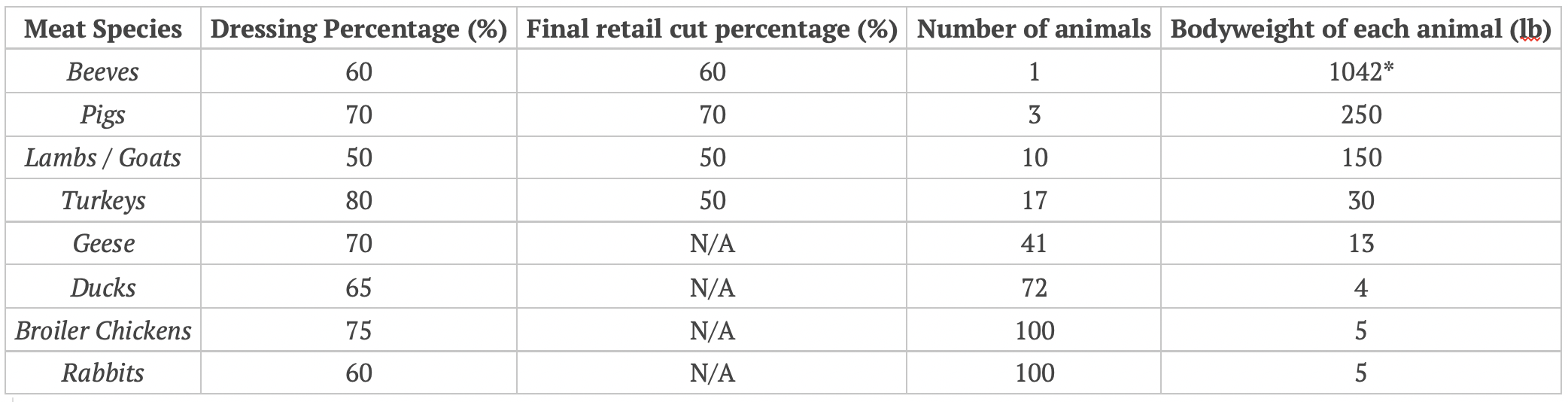

Let’s just see how many animals, of each species, it takes to even make 375 lb of ready-to-cook meat:

*Frame score 3, small-framed beef steer

The next thing to do is to answer the question, how many animals can be raised for a year? Using a “rotational grazing” system on only 1.5 acres, we will assume pastures are productive all year long, and all animals won’t need any other outside supplementation. (This is really tough for pigs and chickens as both are omnivorous and usually need extra supplementation with more protein and energy than forage can provide. Chickens eat some grass but get most of their food from bugs and other little critters. This is equated with pigs on any farm. However, for purely the purpose of demonstration, we will assume that pigs and chickens are living off of grass.)

In the table below, we see the time it takes to raise each of these species to get to slaughter (from birth), how much do each of these animals eat per day (expected amounts are based on dry matter intake on a percent body weight basis), and use those values to see how many animals can be pastured on 1.5 acres for one year only of each species (not combined).

*range. Indicates the range of time to expect an animal to reach slaughter weight.

¥,†See below.

øCalculations based on excellent quality pasture with average forage yield used in Vegan Meme #1 above, which is 10,000 lb/acre production. Rest period 90 days; the amount of time spent in each paddock is 1 day; weight and dry matter intake requirements of each species (see above); and utilization rate is 50%.

§Moderate-framed steer finishing at 1300 lb (calculated at 45.5-day “rest period” increments starting at 600 lb up to 1200 lb).

Having a spreadsheet where I can just plug in a couple of numbers and already have the formulas put in place is all I needed to do to come up with the above numbers. And it’s so bloody helpful, let me tell you!!

How Many Pigs & Chickens can 1.5 Acres of Annual Crops Feed to Slaughter?

Because I feel really bad for forcing pigs and chickens on an unnatural diet of grass-only (they’re omnivores as I mentioned and fed mostly grain, conventionally-speaking), I decided to do some calculations for how many pigs and chickens 1.5 acres can support if those 1.5 acres were corn and soy. According to the Mississippi State University Extension, feeder pigs get about 80% corn and 20% soybean (for simplicity’s sake, not including other ingredients) in their diet. Broiler chickens get about the same.

Using that information, I figured how to divvy up that 1.5 acres so that the land is in both soybeans and corn for one “year” (or growing season), and from there, how many pigs and chickens can be fed off of that.

I figured on 0.5 acres of soybeans and 1.0 acres of corn. The average yields of soybeans and corn are 50 bushels per acre and 168 bushels per acre, respectively. Therefore, half an acre of soybeans would yield 25 bushels (or 1500 lb at 60 bushels/lb), and one acre of corn would yield 168 bushels (or 9408 lb at 56 bushels/lb). That’s a cumulative total of 10,908 lb of grain on 1.5 acres.

A feeder pig is expected to eat an average of 800 lb of feed over the 6 months it takes for it to get to market/slaughter weight. Therefore, 10,908 lb of grain (in that correct ratio of 80% corn and ~20% soybeans) will feed 13 pigs or two batches of 6 pigs over one year (or 365 days).

A broiler is expected to eat a total of 8 lb of feed over the 1.5 months (45 days) it takes for that broiler to reach slaughter weight. Therefore, 10,908 lb of grain (again, correct ratio as with the pigs) will feed 1,363.5 broilers or 8 batches of 170 broilers over one year (or 365 days).

You could probably feed a few more pigs and chickens that are raised on pasture where they have access to other food sources other than their supplemental grain. A “scientific” wild-ass educated guess would be maybe as many as two batches of 7 to 8 pigs per year, or 8 batches of 175 to 180 broilers over one year

How Many Animals can be Fed on a 1.5-Acre Confined Animal Feeding Operation?

As per part b of question 2 above regarding, “How many animals can be raised for meat per year on just 1.5 acres of land?“, let’s ignore the whole pasture-raised thing and just look at this as one ginormous “factory farm” or CAFO (confined feeding animal operation). It’s worth noting that this can easily be done on 1.5 acres.

The table below describes the CAFO-standard space requirements for each species, their associated weights, and the number of animals that can be squeezed onto a 1.5 acre-sized CAFO operation.

These values do not take into account the extra land area that is required to grow these animals’ feed! This is why my choice of words is to “hold,” NOT “support.” “Support” would indicate the addition of growing feed on that same parcel of land to feed those critters.

Therefore, the above numbers are grossly inflated. Just because 1.5 acres can hold (under intensive confinement) hundreds to hundreds of thousands of animals in one year, they don’t support the ability to grow feed for the animals. For most species in that table, hundreds of acres will be needed to raise any one of these types of species up to slaughter.

That means that I have to ignore those values. Because the meme is purely about raising animals on 1.5 acres, I can only use the values I calculated for animals raised on pasture (and the crops are grown for two specific omnivorous species. You know which ones).

Let’s finally answer that pesky question: “How much meat of each different listed species can actually be produced on 1.5 acres?“

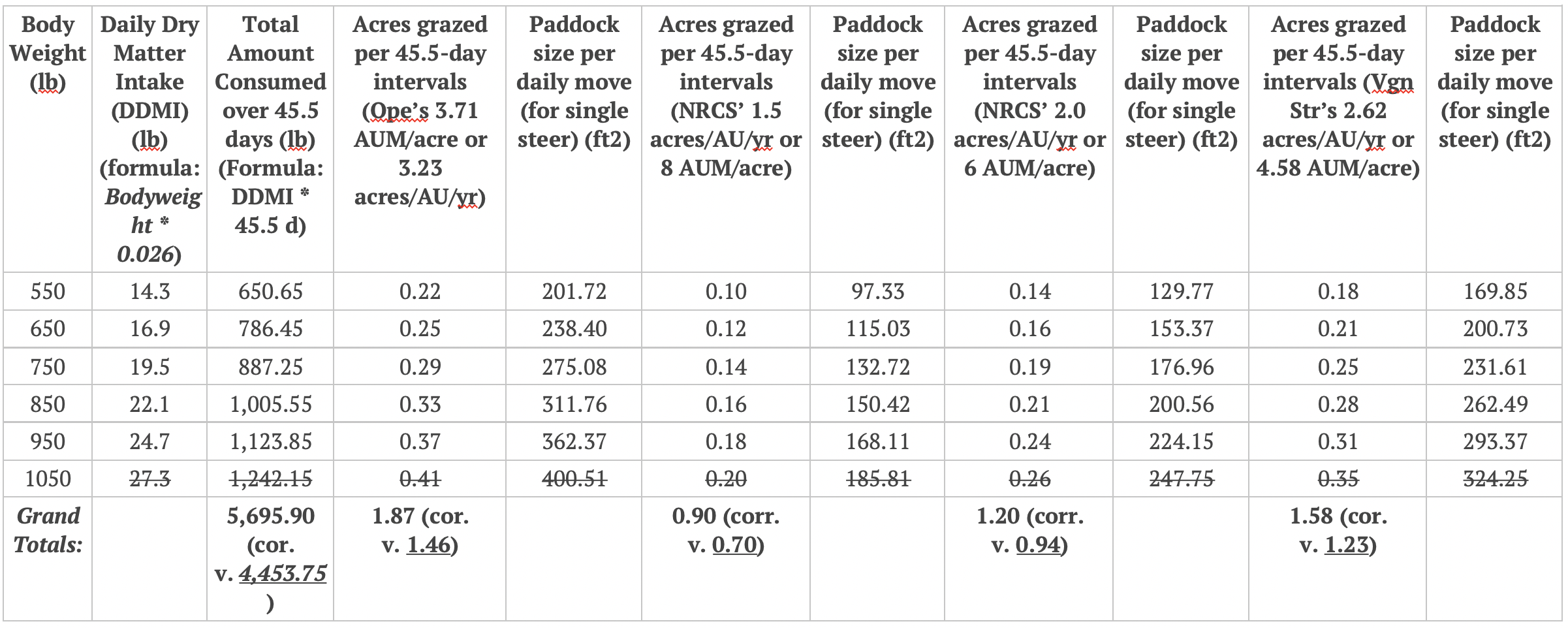

How Much Meat of Each Species can be Produced on 1.5 Acres?

Using the same dressing and cutting percentage weights that I started with, here are the final calculations of the number of each species raised on 1.5 acres (remember this is one of each species, not all combined) on excellent-quality pasture.

Final Verdict:

The Cowspiracy’s 375-pounds-of-meat claim is so far off the mark it’s f**king hysterical.

No doubt that that amount of meat still doesn’t match the amount of plant-based foods that can be produced on 1.5 acres. But then again, when 1.5 acres is on poor quality soil or land unsuitable for growing crops, let alone a garden, those numbers look really, really good. Particularly when you know full well that they’re taking advantage of a resource that we humans wouldn’t even dream of eating ourselves.

But really, where are they coming up with 375 lb of “meat” on 1.5 acres? That’s the next big question I want to answer and figure out, like with the first meme above.

I think we can all agree that it’s actually based on meat from cattle, not the disingenuous term “meat” that was, in my honest opinion, stupidly used.

How did they come up with 375 lb of beef (not meat) on 1.5 acres??

It makes things easier when I can work backwards. Actually, that’s the best way to go!

Just like with the Vegan Street meme, let’s assume that 375 lb of beef is boxed beef; not the dressing weight post-slaughter. So, the actual weight of the animal is:

375 lb of boxed beef ÷ 60% retail weight from carcass weight = 625 lb ÷ 60% carcass weight from live weight = a 1041.6667 lb or ~1042 lb steer or heifer

According to the NDSU Beef Cattle Frame Scores factsheet, a 1042 lb steer is closest to a frame score of 4 for slaughter steers, and 5 to 6 for heifers at the same slaughter weight. This indicates that this steer is “medium/moderate-framed.”

Frame scores (based on hip height measurements which are taken with the age of a bovine) range from 1 (one) to 9 (nine), with one being the smallest. Miniature cattle, I believe, could be smaller than FS-1 cattle… but that’s beside the point.

Most cattle are slaughtered when they reach between 1300 and 1500 pounds. This finishing weight range yields between 460 lb to 540 lb of boxed meat. Those animals are considered to be “large-framed.” This is the standard targeted finishing weight of most North American feedlot production systems in the context of feeding beef cattle aged 18 to 24 months.

Now, to find out how you’d get 375 lb of beef from 1.5 acres, I need to work from the estimated live-weight of the animal (calculated above) so that we can figure out the forage productivity of that 1.5-acre parcel of land.

On the original version of this very post, I erroneously worked on answering that question using only the end-point slaughter weight of the steer. A rookie mistake. Oops. What I should’ve done (and will do in this version) was to start with a recently-weaned steer. In other words, I should have (and will) perform the same steps as what I did above with the Vegan Street meme.

Yet, we all know that the chances of the value I come up with will jive with what good ol’ Ope pulled out from the reaches of his you-know-where.

To work on this and make calculations easier, I will round up the final slaughter weight to 1050 pounds.

The average weaning weight of a medium-framed steer is around 550 pounds.

Knowing that the daily dry matter intake (DDMI) of a growing steer on a percent body-weight basis is 2.6%, and assuming a 100-pound increase over 45.5-day intervals (with an average daily gain of 2.2 pounds), the values I came up with are:

The value above gives us a total consumption over 227.6 days (not a full 365 day period), not necessarily in the goal of getting this medium-framed steer to the finisher weight of 1042–rounded up to 1050–pounds of 4,453.75 pounds of forage. We can use this to get the minimum-expected amount of forage 1.5 acres is expected to produce.

Expecting a 50% utilization of a pasture (where about half is eaten and the rest is trampled and manured on), the minimum amount of forage that 1.5 acres will produce to raise this moderate-framed steer is 8,907.5 lb ( = 4,453.75 ÷ 0.5). To put this in terms of per acre, that equates to 5,938.33 lb/acre.

This is truly ironic. If we’re going to compare this meme to the Vegan Street meme, this forage yield is less than half of what Vegan Street referred to in using the NRCS source! And, it’s a third less than what Vegan Street used to get their 137 lb of beef per acre per year (which I found to be inaccurate). Sooo…

IF again, we are going to compare “like with like,” vegan meme to vegan meme, I ask: which meme is more correct, and which is more realistic? I’ll answer that in the conclusions section below.

To put things into further perspective, the assumed stocking rate for this amount of forage is 3.71 AUM/acre ( = (5,938.33 lb x 0.50) ÷ 800 lb) where 0.50 = utilization rate, and 800 lb = amount that one 1000 lb cow with or without a calf will eat in one month (DM). Or, 114.20 cow-days per acre.

And with that, I’m going to put in a little more time-wasting effort because I did all that work in the previous version where I figured on the number of paddocks, size of those paddocks, and so on to get to a forage yield that ended up being gravely underestimated in the first place.

Not only that, but I’m going to compare just how many acres it takes to grow a medium-framed steer to slaughter using the other three stocking rates from the Vegan Street meme, with the daily paddock sizes thrown in for good measure. It’s all for proof of concept.

This is why I love using tables (tap or click to get a larger view).

This table shows that all (or some) of 1.5 acres is going to be utilized, in a perfect world, to get that medium-framed steer to the target finish weight. The 1.5 acres are not going to be grazed over and over again; no, instead it’s divided into different sections where each gets 45.5 days’ attention via paddocks set up in each section for daily moves per each section.

Again, this is in a perfect-world setting where a person isn’t going to be faced with the issue of “chasing grass.” By that I mean to get grazing that grass stand before it reaches maturity. Grass that reaches maturity is usually seen as lower quality versus grass that is still leafy “vegetative” or just starting to flower. We all know this isn’t a perfect world, and any grazier of any herbivorous species, be it sheep, cattle, or horses, will tell you the same if you ask them about grass.

Realistically, this table still carries inaccuracies. It ignores the fact that grass will grow back after being grazed. In other words, at least one of those sections (I call them “sections”, but they should really be pastures) may be grazed twice or thrice over; in 45 or 90 days they may need returning to. It all depends on what the growing season holds for moisture and growth conditions.

Therefore, it’s possible that half of the total acreage assumed to raise one bovine to slaughter on grass–or a diverse stand of perennial plants, more preferably–will be needed. (Or, half the forage yield is required versus what Cowspiracy claims is needed to get 375 lb of beef.) Therefore, that would make the amount of beef produced on 1.5 acres greater than (perhaps double to) what that meme is claiming. Or, it could support a larger-framed steer than what is estimated.

I used the 45.5 rest period just to make it easier to change body weight by 100-pound increments on my grazing calculator spreadsheet. It doesn’t show how soon grass will grow back, or what the “standard” rest period should be. A producer needs to watch the grass to determine what’s the best rest period to follow, depending on their context.

This meme isn’t totally out to lunch, but it doesn’t reflect the best and highest forage production a pasture could have. The resulting numbers used are actually quite conservative, compared with what Vegan Street meme used as their sources. They’re not as conservative as some other standard stocking rate numbers I’ve worked with before, but when compared with what that NRCS factsheet has…

Vegetable Production of Meme #2

This meme is suggesting that a person can get 37,000 lb of “plant-based food” (fruits, grains, nuts, vegetables, starches, pulses, and oilseeds) on 1.5 acres. To put that on a per-acre basis, that’s 24,667 lb/acre or 11 tons per acre.

I hate to be the harbinger of reality, but that value is very, very ambiguous. It’s not a true reflection of the variability that can be had with the wide variety of cultivated annual and perennial plant-based foodstuffs, annual per perennial. The problem is that there is only one source–not on the meme itself but by being smart enough to go to the Cowspiracy facts page–to which this value is referenced from. If you didn’t check it out yourself, I’ll just flat-out tell you: Vegetables. That’s right, just vegetable production.

What about fruits? Nuts? Grains? Oilseeds? Pulse crops? Perhaps it doesn’t matter because they too can produce a few thousand pounds-worth of products. For instance, the average yield for corn is 9,400 lb/acre; the average yield for soybeans and peanuts is 3,000 lb/acre. Apples average 16,000 lb/acre. Barley and wheat are ~4,700 and ~4,90 lb per acre, respectively. Canola averages at 2,600 lb/acre. Strawberries average 10,000 lb/acre. Almonds, walnuts, and sunflowers average ~2,000 lb/acre. Quinoa ranges from 300 to 2,000 lb/acre. I think I made my point. Don’t rely on vegan memes to get true plant-based food production stats.

This meme provides a very poor example of the potential productivity (or lack thereof) of a piece of land in the context of growing food for both people and animals.

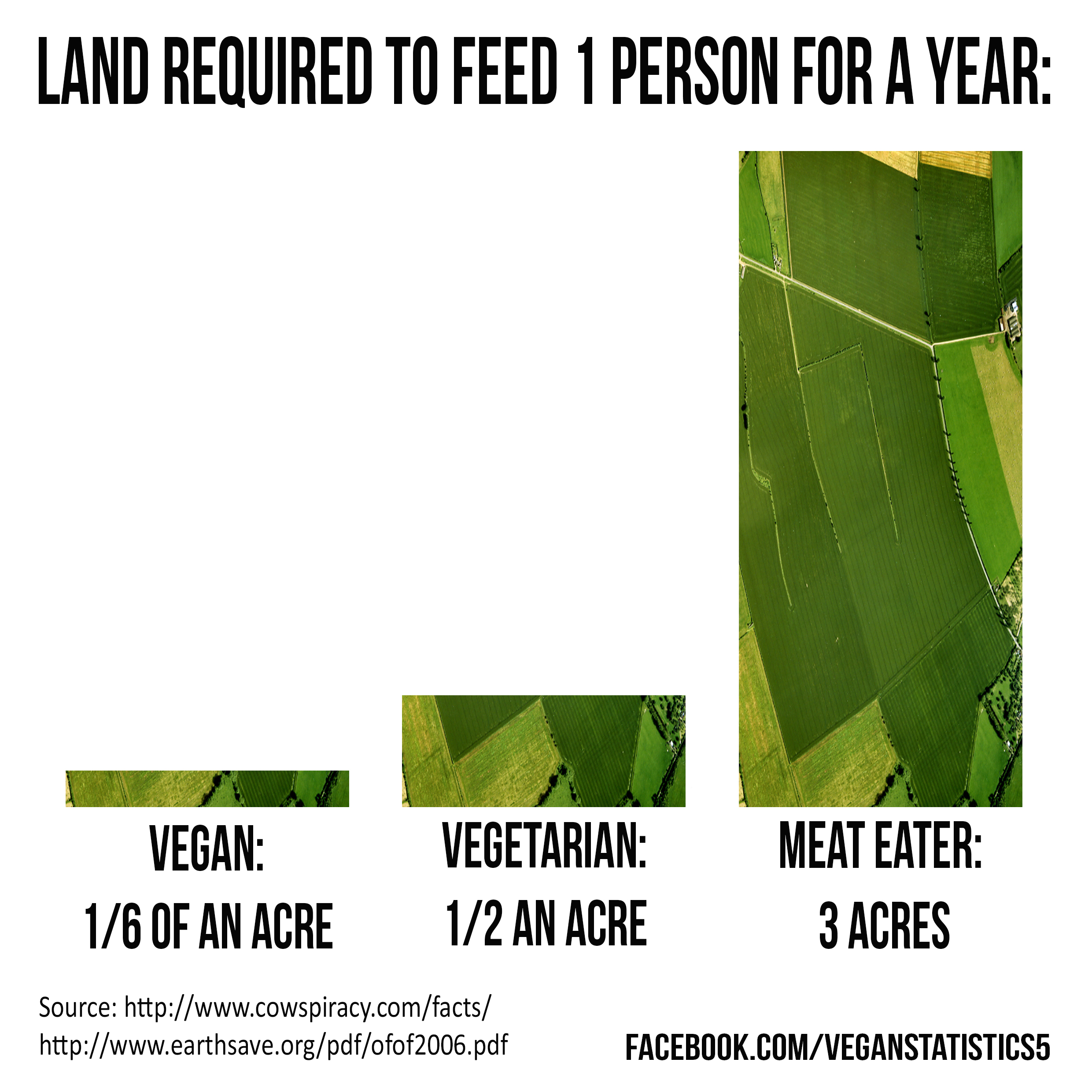

Vegan Meme #3

This is one of the most popular vegan memes on the Internet. If it’s not uploaded on some social media platform–be it Twitter or Facebook, MeWe or Tumblr, it’s used by vegans as a reference in some comment to refute a comment that a “meat-eater” makes about land-use.

There’s just one little inconvenient problem. This meme is a lie. It’s based on 60-year old post-World War II research that has no basis on the vegan diet.

I thought I would have to do a lot of research to prove this. That is until I found THIS page from the vegan website, TalkVeganTo.me who put an impressive amount of work into debunking this meme. Although I disagree with almost all the “facts” they have on their website (and no doubt likewise mine here), I was impressed with the level of research they went into to literally debunk this meme. So, kudos to them!

However, because I too need to thoroughly debunk this meme, I will also refer to the vexingly long chain of sources from whence these values came. There’s no need to plagiarize from TalkVeganTo.me; the chain of sources speaks volumes as they stand.

This meme (not the dietary land-use values) originates from Cowspiracy; it’s another one of their “facts” they’ve made infamous amongst the public forum a.k.a the Internet. Listed as the sources for the land-use comparisons are Earthsave International (a vegan organization) and their 2006 “Our Food Our Future: Making a Difference With Every Bite” propaganda pamphlet (which I’d love to rip apart at a later date… if I ever get around to it), John Robbins’ ©1987 (vegan propaganda) book called Diet for a New America (pg. 352; pg. 344 in the attached pdf), and G. Eshel et. al.’s 2018 paper “Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas, and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs, and dairy production in the United States”; the latter I will discuss in a bit.

Here’s where it gets quite amusing. Do you know where Earthsave International cites this comparison from? You’d never guess.

Mr. Robbin’s 1987 Diet for a New America.

Where does Robbins’ get his information from? (Since he’s the guy who started the whole charade with that silly 1/6th of an acre for a vegan in the first place.) He got it from a 1965 book by Aaron Altschul titled Proteins: Their Chemistry and Politics.

(Robbins also sourced Frances Moore Lappe’s 1982 edition for Diet for a Small Planet [which contains an annoyingly useless and albeit irrelevant excerpt: “...16 pounds of grain has [21] times more calories and eight times more protein…” which has nothing to do with this meme, yet cited Altschul’s book.)

This is what Altschul says, as found by TVTM:

A meat and milk-based diet may require as much as 3 1⁄2 acres to provide one Standard Nutrition Unit.

[…] six to seven standard Nutrition Units of a rice-and-beans diet in Japan are produced per acre. Therefore, depending upon the type of diet, the capacity of the land to support a population ranges from 20:1.

Now, Altschul cited a book for this piece of information from 1961 authored by L. Dudley Stamp called Land Use and Food Production – Hunger: Can It Be Averted? In it, he makes this statement:

Some diets (meat and milk for example) are very extravagant of land; it may require as much as 3.5 acres to produce one [Standard Nutrition Unit equating to 1,000,000 calories or 1 Mcal] whereas a mainly wheat-bread basic diet requires under efficient cultivation only 0.25 acre, whilst the very intensive rice culture together with oceans in Japan produces 6-7 Units per acre. In ‘carrying capacity’ there is thus a range from at least 20 to 1.

Stamp cited his own earlier 1960 book (which is the true original source) called Our Developing World. Here is what he says:

On each acre of farmed land – essentially on a dietary base of rice, double or treble cropped where possible, beans, sweet potatoes and other high Calorie foods – Japan can produce 6 or 7 [Standard Nutrition Units] or support that number of people per acre. Under American conditions, and with a meat-milk-fruit diet essentially extravagant of land, it takes some 2 1⁄2 acres or more to produce one SNU or support one person. It [sic] we then wish to stimulate an argument we can then say Japanese agriculture is 15 to 18 times as efficient as American!

These values are cited from a table that the author of TVTM paraphrased for us:

USA: 175 million population, 3.5 acres cultivated land per capita, 0.4 SNU per acre

Japan: 91.5 million population, 0.15 acres cultivated land per capita, 6.5 SNU per acre

In other words, that source is saying that it 2.5 acres to support one person on the 1960s American Standard Diet of milk, meat, grains, vegetables, and starches, and 1/6th of an acre to support one person under the intensive agricultural practices (plus seafood and fish popular in almost all Japanese dishes). Huh.

The TVTM contributors found that Stamp cited his numbers (albeit indirectly, as they didn’t see where or how Stamp arrived at those numbers) in other parts of Our Developing World from the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (UN-FAO) 1948 to 1952 publication (no mention as to the title of the document) on total food production. He also used the UN-FAO’s 1957 Yearbook to get the total cultivated land acreage.

I believe that TVTM was referring to that Yearbook in where the formulas were used by Stamp to arrive at the values he did:

Country: [Total Harvest Calories ÷ 1 SNU (1,000,000 calories)] ÷ Total Cultivated Acreage = No. of People Diet Feeds per Acre per Year

USA: [X [no citation] ÷ 1,000,000] ÷ 192,500,000 [inferred] = 0.4 People/Acre/Year

Japan: [X ([no citation] ÷ 1,000,000] ÷ 13,725,000 [inferred] = 6.5 People/Acre/Year

There is no doubt whatsoever that the original source has zero correlation with the vegan diet. And yet many vegan sites (including Cowspiracy) and people who label themselves as vegan continue to use that meme and those three land-use comparisons without thought as to where the numbers came from.

Again, kudos to the folks from that referenced site I linked to above for doing a great job on their research efforts.

However, it’s at Eshel et. al. (2018)’s paper that I must part ways with TVTM and begin the disagreements. While Eshel’s paper is well done and very thorough with all the calculations he and his colleagues worked on, there are those inconvenient discrepancies that need to be pointed out. However, I will be as brief as possible with this. This is what they say in their abstract:

Our calculations reveal that the environmental costs per consumed calorie of dairy, poultry, pork, and eggs are mutually comparable (to within a factor of 2), but strikingly lower than the impacts of beef. Beef production requires 28, 11, 5, and 6 times more land, irrigation water, GHG, and Nr, respectively, than the average of the other livestock categories. Preliminary analysis of three staple plant foods shows two- to sixfold lower land, GHG, and Nr requirements than those of the nonbeef animal-derived calories, whereas irrigation requirements are comparable. Our analysis is based on the best data currently available, but follow-up studies are necessary to improve parameter estimates and fill remaining knowledge gaps. Data imperfections notwithstanding, the key conclusion—that beef production demands about 1 order of magnitude more resources than alternative livestock categories—is robust under existing uncertainties. The study thus elucidates the multiple environmental benefits of potential, easy-to-implement dietary changes, and highlights the uniquely high resource demands of beef.

A part that was pointed out by TVTM on the calorie and protein comparisons of beef to plant-based foods is this:

Compared with the average resource intensities of these plant items [potatoes, rice, and wheat] per megacalorie, beef requires 160, 8, 11, and 19 times as much land, irrigation water, GHG, and Nr [nitrogen fertilizer], respectively, whereas the four nonbeef animal categories require on average 6, 0.5, 2, and 3 times as much, respectively.

So I looked into some of the calculations that were made to arrive at these conclusions. Very plainly, it pointed out the fact that these are comparing monoculture, industrial-produced wheat, rice, and potatoes (which have very little, if any, nutritional value to the human diet compared with conventional popular belief) to beef raised on mismanaged pasture and finished in CAFO feedlots.

In other words, Eshel et. al. (2018) are just pointing fingers at beef for being to blame for being so resource-hungry when it’s all to do with how those animals, as well as the resources used to raise those animals, are managed.

These calculations are basically comparing the resources that go into growing wheat, rice, and potatoes for human consumption, versus the resources that go into producing feed for cows. Funnily enough, feed that is comprised of 86% of plant material which we humans wouldn’t even dare to put in our mouths, regardless of its caloric or protein “superiority” to beef itself, or that a fair chunk of that feed is grown on “prime agricultural land that can be hypothetically converted to other crops.”

My argument to Eshel et. al. is how much more photosynthetically efficient are those “other crops”? Are they crops that will remain green all year round (or all of the growing season until the snow arrives) or are they only going to be green, carbon-sequestering solar panels for only 2 months out of the year? How much bare soil will be visible, and how much will be striven to be covered up permanently? How much more biodiverse will those “other crops” be? Will they be drug addicts requesting just a little more fertilizer and a little more pesticide to remain productive and yielding the next year and so on, or will they be helping build soil organic matter and soil biology so that they can be weaned off the chemical-reliant Industrial teat and never have to go back to those inputs again? What about animal impact, in the form of manure and trampling, adding to that SOM protection covering, will those be permitted on those “other crops”?

When will Eshel and his cohorts recognize that cows have legs and can be easily moved from one place to another, without regard for drawing strict boundaries on which area they “most definitely shouldn’t” graze (i.e., those precious “high-quality croplands” he believes should be solely dedicated for soil-mining “food production”) and which areas they, well “could possibly, maybe,” graze; “so long as they’re not hurting wildlife and biodiversity and ecosystem services and… and… and… oh but maybe they shouldn’t graze cuz public lands and wild horsies and cows always hurt the environment cuz they’re non-native alien invaders…” Sorry, I’m being facetious. Seriously, though, it’s ridiculous the lengths people go to blame cows for everything.

I’m getting way ahead of myself.

On to the Next…

In Part 2 of The Beef vs. Vegetable Land-Use Debate, I talk a lot more about this, without needing to name names and point out studies such as Eshel’s 2018 paper (again, links above). I basically point out how management is the biggest issue of all, and finding ways to incorporate livestock in with crop production–regardless of what it is–while healing (regenerating) the soil at the same time is of greatest importance. Basically, I concluded that this pissing contest between beef (or any meat, milk, egg, and fibre) production and “vegan food” production is nonsense, irrelevant, and a huge waste of time.

And perhaps, it’s the “vegan food” production that is causing the greatest amount of damage this world has ever seen. This cannot be seen with quantitative analyses like Eshel’s paper above.

Food for thought.

0 Comments